“When Daniel died there was this sense of relief at first,” he admits. “ We knew how bad it was for him, how much pain he was in. There must be some peace he experienced,” he sighs. “I would’ve given my life it could’ve made a difference.”

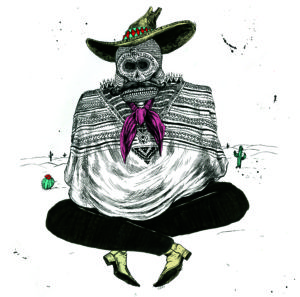

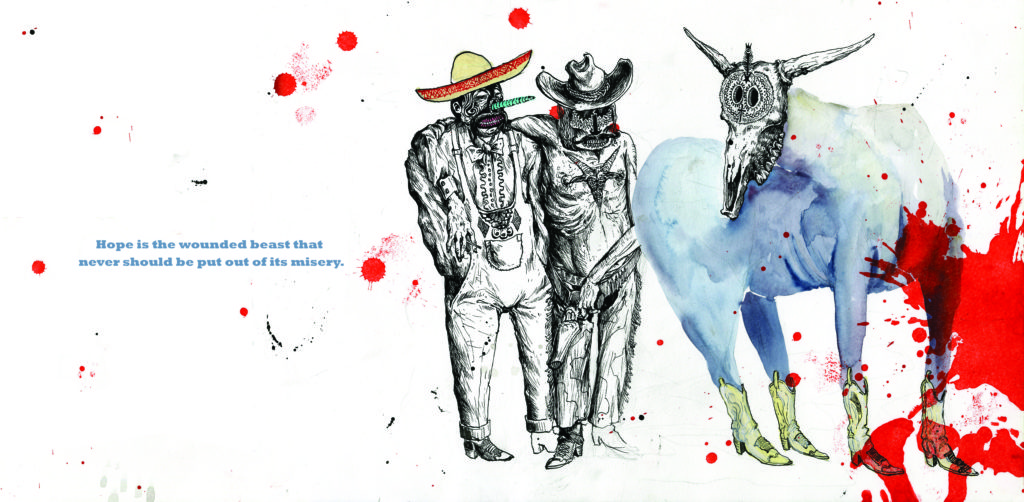

Daniel Levy suffered from depression and possible schizophrenia. He had hallucinations. He was convinced that he was evil and tried to exorcise his demons by taking his prescribed medication, seeking counseling and creating sketchbooks filled with intricate drawings. After several suicide attempts, he finally ended up taking his own life at the age of 21.

Daniel’s drawings, his life and his death, make up the artwork and inspiration for Adam Levy’s first solo effort, “Naubinway”. The album is a testament to both grief and hope. “It is a record about my experience and trying to sort out why all these things happen, why they unfolded as they did,” Levy explains. “The writing was therapeutic for me.”

Even though Daniel’s death suicide wasn’t a shock and it wasn’t an accident, the confusion, sadness and questions still smacked his family into a stunned grief. “Suicide is a disruptive act,” Levy acknowledges. “It leaves huge questions and we have no power to understand it. Daniel’s plane was hijacked somewhere. I can’t lay the blame at his feet.”

For a year, Levy couldn’t even use his music to cope with the pain.“I knew right away that I wanted to write about it. But, I didn’t feel I had a way of doing it without doing with sounding trite and predictable,” Levy developed the first words of “Naubinway” as blog entries as he patiently waited for the language of healing to come.

The result is an album that is both sad and beautiful. Be prepared to feel deeply when you listen. Levy doesn’t spare his emotions and wants to bring the listener with him on his journey. “I don’t want to soft pedal the expression of alienation and pain, but music can transcend that feeling of alienation. Come with me through this dark tunnel and we’ll feel better afterwards,” Levy promises. “I want to give you a glimpse of the pain in the hopes that you’re going to take something away.”

The album features a 32-page booklet of Daniel’s drawings, which offer an insight into this struggle. Clearly, he was both talented and distraught, with a sensitivity and pain that shines brightly in the artwork.

Through the therapeutic process of writing, recording and performing the songs from “Naubinway”, Levy has begun to heal and focus his grief into a sense of purpose to speak out for people with mental illness. “Sometimes I think Dan’s death was sort of a sacrifice,” Levy explains. “ He needed to do what he did so that awareness around mental illness could be increased.”

Levy wants to open up a public conversation about the struggles of individuals dealing with mental illness, which disproportionately affects the Jewish community. According to a study conducted in 2013, Ashkenazi Jews are 40 percent more likely to develop schizophrenia and similar diseases than the general population.

“There’s a groundswell in the media now to start acknowledging that mental illness is a physical illness,” Levy says. He wants to ensure that other children get better treatment than his son did.

“There is still a stigma around mental illness, but the tide is beginning to turn.” Levy is open about his own diagnosis. “I don’t have the equipment to feel embarrassed about being bipolar. I never thought I was a worse person or was weak because I suffered from mental illness.”

Levy attributes his progressive attitude to his grandmother’s activism in the mental health community. She fought to ban straight jackets in the 1940s and 50s. He has taken up the thread of her cause, with a willingness to talk openly about the very real pain that mental illnesses inflict, using his own experience as a starting point.

His vocal opposition to mental illness as a “taboo” topic has already put him in demand as a speaker across the country. “On November 8th, he will be the keynote speaker at 15th Annual Conference on Mental Health presented by the Twin Cities Jewish community. Levy will perform songs from “Naubinway” as part of his address. The conference is free and open to the public.

“There’s a groundswell in the media now to start acknowledging that mental illness is a physical illness,” Levy says. He wants to ensure that other children get better treatment than his son did. He wants to see the medical community treating mental illness with the same care as physical illnesses.

Above all, Levy wants to create more hope. That’s the whole point. That’s the kernel of bright truth underneath the grief and sadness.

“Essentially, the most important thing about being human is hope,” Levy leans forward. “I’m here. I’m hopeful about life. We can get through this. My tale of life does. “

Adam Levy will play songs from “Naubinway” at an in-store show at Electric Fetus in Minneapolis on Wednesday, November 4th.

Ret nypd detective gone through suicide of sibling and cousins daughter 10/22/10 feel free call Lou Pomponio 9177496701 for Adam