In the weeks after George Floyd was murdered by now-former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin, a reckoning with police violence and systemic racism played out across America, including for American Jews.

Twin Cities rabbis and cantors participated in interfaith marches to George Floyd square. The Jewish Council for Public Affairs, the national umbrella organization for Jewish community relations, called “to institute sweeping reforms in law enforcement and the criminal justice system” in a statement signed by 130 organizations, including the Jewish Community Relations Council of Minnesota and the Dakotas.

“Since the killing of George Floyd, more organizations, Jewish or not, are paying more attention to the impact of policing on, particularly, black communities,” said Sheree Curry, a freelance journalist and a Jewfolk, Inc. board member.

But the ensuing conversation about police reform, driven by calls to defund or abolish the police, put American Jews in a bind: After years of rising antisemitism and unprecedented attacks on Jews, like the shooting at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh that killed 11 worshippers, Jewish institutions and law enforcement have a closer relationship than ever before. As a result, many communities focused their reckoning on concerns from Jews of Color about the presence of law enforcement at Jewish institutions and avoided a larger reevaluation of their relationship with police.

The COVID-19 pandemic also played a role. “A lot of synagogues were able to avoid a hard conversation about police for a while because we all have been on Zoom,” said Carin Mrotz, executive director of Jewish Community Action.

Now, though, times are changing in the Twin Cities. Increased vaccination rates have meant a return to in-person Jewish life. And during city elections on Nov. 2, voters will decide the future of the Minneapolis Police Department for the roughly 430,000 residents of the city — which includes a quarter of the Twin Cities area Jewish population. Jewish institutions may soon have to reassess community security in step with the city.

If the Yes 4 Minneapolis ballot amendment passes, the Minneapolis Police Department will be removed from the city’s charter along with its mandatory funding minimum (Minneapolis is the only city in Minnesota where police are in the charter). In its place, a Department of Public Safety will be established with the potential to include not only police, but also social workers, mental health experts, and housing professionals as part of law enforcement. The MPD would operate normally until the transition is complete.

There are few specifics of how the Department for Public Safety will operate if enacted. City officials were prohibited by the Minneapolis Ethics Officer from publicly detailing plans for the department, lest it look like a campaign in support of the amendment. From a mainstream Jewish security standpoint, the uncertainty is concerning.

“I deeply worry a movement to public safety would impact, and not necessarily in a positive way, the Jewish community,” said Yoni Bundt, CEO of Masa Consulting, who has worked with law enforcement and Jewish organizations on crisis response. “There’s too much unknown and too much unknown creates risk.”

For Jewish activists, the uncertainty is a chance to bring accountability and change to an unpopular police department that has resisted reforms. It is also an opportunity for local Jews to look broadly and critically at our community’s reliance on law enforcement for security. Law enforcement institutions have a long history with white supremacy — an ideology that threatens all minorities, including Jews — which was brought into renewed focus after the Jan. 6 insurrection in Washington, D.C.

“I don’t know how we can rely on a state institution, and at the same time, not be able to interrogate — like, we question God. So how can we not question this institution?” said Enzi Tanner, the community safety organizer for Jewish Community Action. JCA is part of the coalition advocating for the Y4M amendment.

Historically, Jews have been targeted and oppressed by governments using police, said Mrotz.

“We all have that joke, right? Who among our friends would hide us,” Mrotz said. “But hide us from whom? Because what we’re saying [now] is, actually, we’re just gonna call the cops, we’re not worried about calling the cops and what danger will befall us.

“At what point did we start trusting police?” she said. “When did that happen?”

The 20th century

In 1923, The American Jewish World warned about the growing influence of the militant white supremacist Ku Klux Klan.

“Just as generals during war aim to capture strategic positions, so Klan organizers try to obtain membership where the organization can sway its greatest influence,” the article reads. “Thus in every community the membership drive is aimed with the greatest intensity at offices connected with the enforcement of law.”

The article concluded that the KKK was very much present but “not well organized in the police department; there are too many Irish,” while finding more of a foothold in the Hennepin County Sheriff’s department. The one local law enforcement agency seen as definitively KKK-less was the Hennepin County Attorney’s Office, headed by Floyd B. Olson.

Olson, a non-Jew, grew up in North Minneapolis and was so friendly with the Jewish community that he spoke Yiddish fluently. In the 1930s, he would also become governor of Minnesota and bring a network of Jews into state government.

This is the dichotomy that Minneapolis Jews — for much of the 20th century, the majority of Twin Cities Jewry lived in North Minneapolis — experienced in their relationship with law enforcement: On one hand, they dealt with police and other agencies infiltrated with racism and antisemitic ideology. On the other hand, they had a distinct relationship with the officials in charge of policing.

Mayor George Leach and Minneapolis Police Chief Frank Brunskill were featured speakers at the 1927 dedication ceremony for the Mikro Kodesh synagogue building. Minneapolis police chiefs would continue to be invited to Jewish events. And there were Jewish officers in the MPD, like Martin Ginsburg, the second-ever Jewish member of the force.

These high connections did not protect Jews on the streets, however. Sam Freedman, a professor at the Columbia School of Journalism, found “multiple examples of police bias against Jewish residents from the 1920s through 1940s,” he said in an email. Freedman researched the incidents as part of a forthcoming book about Hubert Humphrey.

“Jews were absolutely viewed by all parts of the power structure, including the police force, as outsiders,” Freedman said, “which gave a relatively free pass to cops who harassed and intimidated them.”

A notable example of police bias is in 1944-45, when Jewish kids in North Minneapolis were “waylaid and beaten after being asked if they were Jewish,” reported the AJW. The acting chief of police dismissed the attacks as “boy trouble” and the police were criticized for their poor response.

But in the complicated Jewish relationship with law enforcement, there was also another element: The Jewish mafia.

Isadore Blumenfeld, better known as Kid Cann, was the “closest thing Minnesota had to a godfather.” Cann operated with the tacit approval of law enforcement, and when a journalist criticized Gov. Floyd Olson for alleged mafia connections in the 1930s, Cann murdered him. And David Berman, Cann’s rival, was an influential donor to Mayor Marvin Kline in 1941. When Jewish publisher Arthur Kasherman criticized Kline for corruption, he was also murdered.

The Jewish mafia did not represent the local Jewish community. But “the fact that Jewish mobsters…were active in Minneapolis was extrapolated [by police] to mean that Jews as a whole were implicated in crime,” Freedman said.

After WWII, chronic antisemitism in Minneapolis began to fade. This also meant a better relationship with law enforcement, and the 1960s would mark the next major chapter for the Jewish community and police.

In the last weekend of 1961, Jewish institutions were hit with a wave of swastika graffiti that included slogans like “we are back again.” A Chicago synagogue had also been bombed. Minneapolis police were quick to respond: Chief of Police Pat Walling assigned detectives to North Minneapolis to investigate. Mayor Art Naftalin (Minneapolis’ first Jewish mayor) announced that MPD was creating a Community Protection Unit to address the incident. And with the approval of the MPD, the local Jewish War Veterans association set up patrols around Jewish institutions.

The patrols sparked a minor community crisis. Rabbi Bernard Raskas, of St. Paul’s Temple of Aaron, said the patrols were making a bigger deal out of the graffiti than they were worth.

Other minorities’ buildings “are constantly smeared and they seem to need no special guard,” Raskas wrote in TOA’s bulletin. The patrols made the police look bad by implying they weren’t working to protect Jews, he complained. And the rabbi questioned how often members of the Jewish War Veterans prayed and gave donations to Jewish causes, saying “lets stop playing soldier and start being men.” The veterans were furious and demanded a retraction.

In the Civil Rights era, both the graffiti and bombings were a defining feature, and across the country, the incidents created more trust between Jews and law enforcement. In the South, 28 police departments created a network for addressing synagogue bombings after the 1958 Reform Temple bombing in Atlanta by white supremacists. But the response also showed the stark divide in how law enforcement treated Jews and Black Americans.

“The terrorist attacks against the Temple prompted an outpouring of public sympathy and immediate intervention on the part of local and federal officials,” wrote historian Clive Webb. “Although African Americans had suffered far more assaults on their homes and churches, the authorities had reacted with indifference to most of these outrages.”

In Minneapolis, trust in police also improved as Jews became more concerned about the deterioration of the North Side. Many Jews feared — falsely — that the presence of Black Americans and institutions created slums.

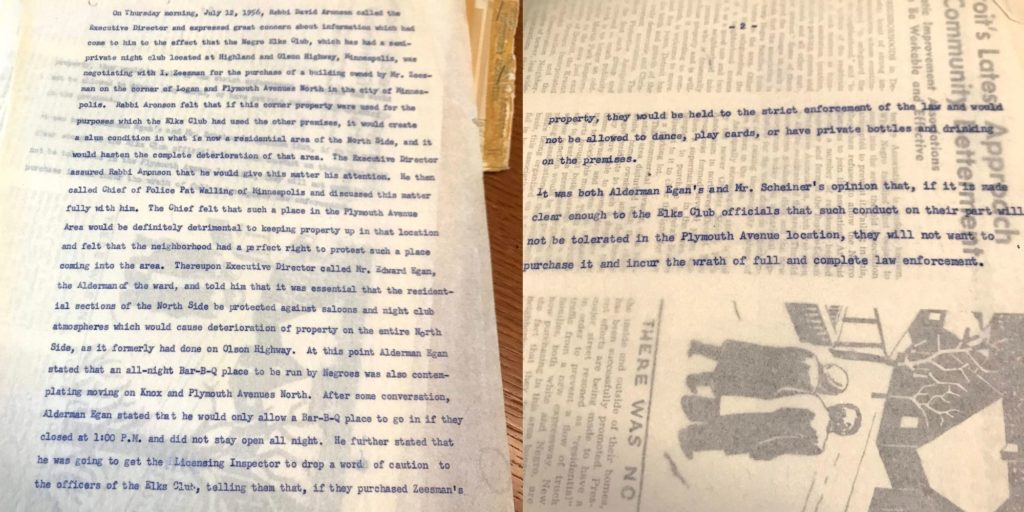

That fear animated Samuel Scheiner, executive director of the Jewish Community Relations Council of Minnesota and the Dakotas, to work with the chief of police in 1956 to stop a Black-owned nightclub and a Black-owned barbecue restaurant from moving to the North Side. Scheiner acted after a call from Rabbi David Aronson, of Beth El Synagogue.

Samuel Scheiner’s write-up on efforts to stop Black businesses from moving to the North Side in 1956 (courtesy of Russel Star-Lack).

In the late 1960s, the North Side erupted in several Black uprisings protesting police brutality, racist city policies, and discrimination. Shops and businesses, many of them Jewish, were burned. Police were seen as protectors of law and order on the North Side, which reflected across Minneapolis when Charles Stenvig, a police officer, was elected as mayor in 1969.

Stenvig was a right-wing populist who said he would “take the handcuffs off the police,” creating a lasting legacy for a police department that would resist reforms and target African Americans. He also formed a close relationship with the Jewish community, participating in high-profile mayoral trips to Israel and attending local celebrations of the Jewish State.

“Scheiner viewed post-uprising North Minneapolis as a warzone that was particularly dangerous for Jews,” Russel Star-Lack, a housing activist who researched Scheiner’s archive to write about Jewish migration from Minneapolis to the suburbs, said in an email. As a result, “Scheiner was very appreciative of [Stenvig’s] crackdown on North Minneapolis.”

The 21st Century

In August 1999, a white supremacist wanted to give “a wakeup call to America to kill Jews.” So he brought a gun to the North Valley Jewish Community Center in Los Angeles. Seventy rounds and five injured victims later — including a 5-year-old attending the JCC’s summer camp — he fled the JCC, stole a car, killed a Filipino mailman, and then turned himself in to the FBI.

The attack marked an already terrifying summer for American Jews. In June, Sacramento synagogues were firebombed. In July, a white supremacist attacked in Chicago, injuring several Orthodox Jews and killing a Black former Northwestern basketball coach and a Korean graduate student. The Jewish Telegraphic Agency declared “a climate of fear among Jews unseen in this decade.”

That summer defined the threat that continued chasing American Jews deep into the next century: Difficult to predict lone-wolf terrorism. In time, it would drive Jewish communities across the country to embrace a closer relationship with law enforcement in the pursuit of safety.

But early on, Jewish institutions did not rush to increase security.

“You couldn’t get lay leaders of synagogues or even the professional leaders to say, we need to invest in strategies and tactics about keeping our buildings and our people safe,” said Bundt, the crisis response consultant who has worked with a variety of institutions, including law enforcement and Jewish organizations. Many Jewish institutions were focused on being welcoming and open, unfortunately at the expense of security, he said.

In the Twin Cities, “JCCs and synagogues began constructing walls inside their playgrounds,” recalled Steve Hunegs, executive director of the JCRC. But there wasn’t yet familiarity with the scope of the threats.

“These murderous, terrible incidents occurred at a different time and place, and one in an American society where perhaps they were seen as more anomalous or outliers,” Hunegs said. “In a time when the culture wars, the level of hateful discourse, while present, was significantly lower than it is in 2021.”

Serious investment in security came after the 9/11 attacks in New York City. The Jewish Federations of North America lobbied Congress for funds to protect religious nonprofits. In 2005, the Department of Homeland Security began offering the Nonprofit Security Grant, and in its first year, half of the $25 million in grant money went to Jewish organizations. JTA reported that they “asked for barriers, reinforced doors, blast-proof windows, security cameras, gates and fencing.”

“That constituted a major investment in the religious community’s ability to obtain funds for security, which helped catapult that need even more to the forefront,” Hunegs said.

More attacks caught Jewish concern, though they still looked like isolated incidents. In 2006, a Muslim man, claiming to be upset about the American war in Iraq and military aid to Israel, took a 14-year-old girl hostage and used her to enter the Jewish Federation of Greater Seattle building. He shot six people, killing one, and asked a 911 operator to contact CNN before surrendering.

In the next decade, attacks on religious institutions seemed to be more deadly and more common worldwide, noted Hunegs, worrying the Jewish community.

Then came the defining event for Jewish security: The 2018 Pittsburgh attack. A man targeted the Eitz Hayim, or Tree of Life, synagogue for being associated with HIAS, the Jewish refugee agency, at a time when the president of the U.S. and right-wing American media were stoking racial fears about immigrants, refugees, and asylum seekers. It was the deadliest ever attack on American Jews, leaving 11 dead.

Temple Israel was full with attendees at a vigil on Oct. 28, 2018, for those murdered at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh. (Photo by Lonny Goldsmith/TC Jewfolk)

It “marked the demarcation of time. There’s Jewish communal security before, and there’s Jewish communal security after Eitz Hayim,” Hunegs said.

Relationships and Dilemmas

Recently, the Twin Cities was reminded of the need for law enforcement when Beth El Synagogue was threatened with violence.

Within hours, St. Louis Park police and the FBI were investigating. Police “were instrumental in providing a sense of security,” said Beth El’s Rabbi Alexander Davis. The response was a hallmark of the close relationship between the synagogue and police.

A St. Louis Park Police mobile camera setup in the parking lot of Beth El Synagogue on Friday, Sept. 10, 2021, after threats made against the synagogue.

A mantra of community security is not to meet law enforcement, or other crisis responders, for the first time during an incident — there has to be an established connection beforehand. “While the Jewish community has successfully developed its own security institutions, the bedrock is law enforcement at all levels,” Hunegs said. “We only have so much capacity.”

But while firmly grounded in the need for security, the community’s relationship with the police is also defined by a variety of tensions and dilemmas. Most prominently: How do you balance security with the concerns of Jews of Color, many of whom, already profiled by law enforcement on the regular, don’t feel comfortable with security guards at Jewish institutions?

For Tanner, the community safety organizer for JCA, high holidays are a uniquely stressful time as many synagogues increase security and hire guards.

“Fear is interesting, in the way that if you watch a scary movie, it’s not real, but your body responds as if it’s real,” he said. “I’ve had nothing but negative interactions with police officers in Minneapolis…so for me, I remember times going to high holidays and being like, do I have the capacity…to actually stay during services?”

Rafi Forbush, the founder of the Multiracial Jewish Association of Minnesota, has been profiled and stopped by police when going to synagogue. When he told that story, “people would try to give me a solution of what I could do better. And that was, ‘well, you should approach the police car, and you should introduce yourself,’” he said. “In that moment, I’m thinking, right, but you didn’t have to, nobody else had to, why is that part of my holiday routine?”

But after working on Jewish security in the Twin Cities, Forbush thinks there needs to be a closer relationship with law enforcement. More familiarity between Jews of Color and police will help with trust, he said, and despite the frustration of being told to introduce himself to police, for Jews of Color it’s “the chicken or the egg, right? Who does it first?”

“We’ve had a lot of allies and supporters stand up in the Jewish community and say, the idea of uniformed officers and squad cars makes me extremely uncomfortable,” Forbush said. He agrees with the push to talk about how communities are welcoming Jews of Color, “but let’s not get anything twisted, we need law enforcement involved in our community.”

That need is also complicated by the fact that having close ties to law enforcement means being close to an institution with longstanding issues of right-wing extremism, use of force, and lack of accountability. For many, those issues just reinforce the need and utility of engagement, rather than being a reason to question ties with police.

“We don’t necessarily base our relationships [with law enforcement] on the things that are wrong,” said Rabbi Neil Blumofe, head of the Agudas Achim congregation in Austin, Texas. “There’s always the opportunity to educate, uplift, and do better.”

Austin, in some ways, parallels Minneapolis. Both cities have seen a drop in the number of police officers over the past year, and are experiencing the rise in violent crime that has swept the country. Both cities also have high-profile amendments related to policing on the ballot for local elections on Nov. 2. But the emphasis on relationships for minority communities, as the best way to help with law enforcement accountability, remains the same.

Blumofe is close friends with the Rev. Daryl Horton, pastor at the Mt. Zion Baptist Church, a Black congregation in Austin, and they help each other connect with local law enforcement. “I’m not naive [enough] to believe that my personal relationship with the chief of police is going to end the racism in the department, I just know that it’s going to have to happen a person at a time,” Horton said. “How do you develop a strong favorable relationship with an organization that has proven in the past to not have your best interest at heart?

“I think [for] any leader in the faith community, even within the Jewish community, this is a huge burden to take on — if you want to have that relationship make a difference.”

In Minnesota, the JCRC has focused on the educational opportunity in bringing members of law enforcement to tour the Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C. There’s a special tour for law enforcement and members of the military that focus on how those institutions helped the Nazis rise to power.

The tour has “all sorts of questions about the way that the law enforcement and the military perform their jobs, what orders are legitimate to follow, how they conduct themselves with other people, and how they treat minority communities,” Hunegs said.

“We rely upon institutions which have at times struggled with their own internal extremism. So let’s try to be helpful, as opposed to simply defaulting that this is how it is,” he said. “It’s our experience that the positive nature of the relationship significantly outweighs any issues that we’ve seen with extremism in the police or the military.”

Still, not everyone has faith in the incremental change that close ties with law enforcement might bring.

“We have been talking about [police] reform for a very long time,” Tanner said. He lives in Minneapolis, “and every three years, there’s a conversation about reform that doesn’t happen. Our Jewish mayor has said that he’s done reform, even though people keep dying [under] his leadership.”

Public Safety Beyond Policing

For all the talk about police reform in the Twin Cities due to the Yes 4 Minneapolis amendment — and about law enforcement in this piece — the bigger picture is less about cops and more about deciding how to get a grip on crime, poverty, homelessness, and other societal ills.

“What do cops have to deal with? All the things in society that society doesn’t want to manage and deal with,” Bundt said. Former Minneapolis Mayor Betsy Hodges has said the same.

“Police reform feels like a band-aid and doesn’t really change the material conditions that most people are living in,” said JCA’s Mrotz. In some sense, supporters of the Y4M amendment are trying to address these broader issues via the proposed Department of Public Safety by integrating housing and addiction experts to help people. But even if the amendment passes, it isn’t the end-all, be-all of Minneapolis’ problems.

The amendment “only gives us the ability to actually change something,” Tanner said. “It doesn’t actually mean that we’re changing something, we’re just changing some words” in the charter. The rest would be up to the mayor and city council.

If the amendment fails, it could be back on the ballot in future years. And while some in the Jewish community might worry about what comes next for local law enforcement and our security, it’s important to remember that we are not the only community concerned about changes, Tanner said.

“We can’t earnestly engage in that conversation if we are not able to say, this is not unique, that the Jewish community has been…intentionally under attack the last four or five years. But that’s not more than the fact that Black folks have been under attack for the last four or five years, Asian folks,” he said.

“We’re not that unique in this marginalized piece.”

Thank you to Lev and TC Jewfolk for providing this thoughtful, detailed, and nuanced post. I think this history and the diverse current perspectives are important for TC Jewish community members to hear and consider.