“Sara, we have a problem,” he told her.

Slager had left New York to spend that Shabbat with his family in St. Louis Park and be called to bless the Torah as a soon-to-be bridegroom. But seeing that New Jersey and New York were about to be on lockdown due to COVID-19, he canceled his flight back and called Elspas about rescheduling their wedding, which was planned for March 29 for a venue just outside Teaneck, N.J.

“I was just sitting in a chair with my heart beating, and I was thinking, ‘oh no, we’re not getting married, this is the worst day ever,’” Elspas said. “It was awful.”

The next day, she flew to Los Angeles where her family is. For the next week, that of March 16, the wedding plans changed daily.

“We were trying to beat the clock, so to speak,” Elspas said. “Because we really really wanted to get married…and we were thinking, because everything with the virus was moving so fast, that if we don’t move it up, then things are going to change.”

Seeing that Minnesota was behind California in the number of COVID-19 cases, the couple decided that their best bet would be to get married here on Tuesday, March 24. And though L.A. was locked down with a stay-at-home order by the mayor on March 19, Elspas managed to fly to Minnesota for the wedding.

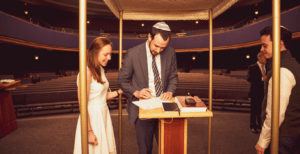

Now, Sara Elspas is Sara Slager after an intimate ceremony at Semple Mansion in Minneapolis. Though just 20 people physically attended, roughly 260 computers were logged into the wedding’s Zoom livestream, which Toviya Slager estimates to mean that anywhere between 300-400 people were watching.

“It turned out beautifully,” Toviya Slager said, “and a lot of people said it was nice that they got a front-row seat, because most people don’t get to see that front-row view of a wedding, usually.”

Three weeks have passed since synagogues in the Twin Cities began shutting down in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, leaving families, congregation members, and communal leaders in the uncharted waters of a Judaism without physical community.

Services, classes, and meetings transitioned online with relative ease — often into the multiple screens of Zoom or the live video feature of Facebook. But essential Jewish rituals have not had it so easy.

“You’re trying to map [rituals] out literally by the seat of your pants,” said Rabbi Joshua Borenstein, executive director of Torah Academy in St. Louis Park. “God took the playing board and flipped it upside down.”

Children who prepared for months, or even years, for their bar or bat mitzvah are unable to step onto the synagogue bimah to celebrate their Jewish adulthood. Baby namings are delayed, and parents with a newborn boy are squeezed for time and safety considerations when deciding how best to do brit milah, the ritual circumcision.

Sonya Uha and Jacob Rapport at their wedding in an empty sanctuary at Adath Jeshurun Congregation (Photo courtesy Sofya Barth/sofyB&B Photography)

Rabbis are guiding people through end-of-life prayers over FaceTime, officiating funerals over Zoom, and grappling with how families should do ritual mourning. And weddings have become somewhat of a free-for-all, with dates and ceremonies moved around, and the search for refunds added to the overall stress of living through a pandemic.

So TC Jewfolk spoke with clergy, community members, and Jewish professionals for a deep-dive about how these four rituals – B’nai mitzvah, brit milah, weddings, and burial/mourning rites – are being reshaped during the pandemic across denominations and communities in Minnesota.

In Minnesota, most weddings have been postponed, with some rescheduled for 2021.

But the Slagers aren’t the only couple to move up their ceremony. Some clergy at the conservative Adath Jeshurun congregation in Minnetonka were surprised one mid-March afternoon to learn that a wedding was taking place in the sanctuary, as they were clearing out the building in preparation to shut it down.

“It was kind of a ritual MacGyver moment,” said Hazzan Joanna Dulkin.

Because the Jewish marriage document, the Ketubah, was already signed, the couple decided to do half of a Jewish wedding and sign their civil license instead.

“So they’re civilly married, and Jewishly they are officially betrothed to each other,” Dulkin said. “It was just an absolutely impromptu and absolutely gorgeous wedding…and it totally made our whole week.”

B’nai Mitzvah On Hold

While the rulebook for weddings has been, in many cases, thrown out, bar and bat mitzvah ceremonies during the pandemic are generally experiencing one rule: Delay.

For some kids, a delayed ceremony could have them reading the Torah or Haftorah portion they were already going to read on a different Shabbat a few months from now, once the pandemic is over.

Some rabbis have also offered the option for kids to read their Torah or Haftorah portion on the livestream of Shabbat services that many synagogues have. But families are largely choosing to pass on that.

“We are giving people the choice, whether they want to go online and do it that way, and everybody has decided no, that’s not what they want to do,” said Rabbi Marcia Zimmerman, senior rabbi at the Reform Temple Israel in Minneapolis. Despite Zoom, “there was no way they wanted to do it without the people they loved being there.”

Conversations with families are still a work in progress.

“We’re working individually with each family to honor the work that the kids have done,” Dulkin said. “At this point in this situation, I’m very loath to tell people that there’s one right way to do something. The truth is we’re all figuring it out as we’re doing it.”

Balancing Religion, Health Needs

As clergy feel the pressure to adapt Judaism during a pandemic, parents with newborn children, and particularly newborn boys, will have to decide what to do about brit milah.

Ritual circumcision is mandated by Jewish law to happen when a boy is eight days old, as a sign of the Jewish covenant with God. But what’s the best way to balance religious needs with current health needs?

For now, Minnesotan mohels, the professionals trained to do brit milah, are encouraging families to have the ceremony as intended. Although, if parents are concerned, they should, of course, discuss with their rabbi and doctor.

“My approach has been to try to say, let’s do the bris, but keep it as small as possible,” said Dr. Robert Karasov. “I may have to rethink that as the pandemic progresses; really the only people that need to be there are the parents and the mohel.”

If parents aren’t comfortable having the mohel at home for the ceremony, then they should plan ahead, say the two mohels interviewed for this story. The next best option is, if the baby is born in a hospital, to have the staff there do the circumcision.

That won’t count as a brit milah. But with the circumcision done, a ceremony called hatafat dam brit, or the drawing of the blood, can be done after the pandemic to complete the ritual.

Completely delaying the circumcision is the last option, but not a favored one.

“One thing that I think we really want to try to avoid is postponing circumcision until after the pandemic,” said Dr. Laurie Radovsky, “because then you’re looking at possibly doing it in the hospital with anesthesia. It’s a much bigger deal.”

According to Radovsky, some insurance companies don’t cover circumcision, and even those that do can be picky about when and where the circumcision is done. The medical procedure is much cheaper when the baby is a newborn. In part, this is because the operation for babies that are several months old is usually done with general anesthesia in a hospital.

But the hospital circumcision option for newborns may be disappearing. As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, cases increase, and hospitals become overwhelmed, many hospitals are canceling elective procedures – which could include circumcision.

Karasov spoke of one soon-to-be mother who was told the hospital where she plans to give birth won’t be doing circumcisions. It’s unclear how many hospitals in Minnesota have made this decision.

The religious, financial, safety, and hospital regulation squeeze is particularly difficult to navigate. “It’s kind of stressful trying to think, am I doing the right thing; there’s really no great guidelines,” Karasov said.

Said Radovsky: “It’s on top of everything else we’re all going through: Being stuck in our houses, worrying about having enough toilet paper. One more thing to be sad about in how [the pandemic has] impacted our ritual life.”

Still, there are some upsides to the more intimate brit milah ceremonies that have been done during the pandemic, Karasov said.

“To be honest, I think its been very sweet…sometimes when you have a big crowd that’s a certain kind of celebration and a certain kind of joy, but it’s sometimes a little overwhelming for families,” he said.

Of course, family, friends, and a rabbi still followed along with the ceremony over a livestream.

Expressing Grief

Burial standards in the Jewish community have been through somewhat of a whirlwind.

Last week, when Teri Bretz, a funeral director at Hodroff-Epstein Memorial Chapels, was interviewed, the funeral home was doing burials with a rabbi and a few family members at the graveside.

“It’s rather heartbreaking to see a burial take place with minimal family members able to attend,” Bretz said then.

“Its certainly been so difficult for us to have to go to these guidelines,” she said. “But Judaism also talks about the importance of health for the living…so, of course, you have to balance that, and this is just where we are right now.”

Earlier this week, the Minnesota Rabbinical Association decided that it is safer for all clergy and mourners to remain at home and view the burial over livestream, with only mortuary professionals at the graveside.

Agreeing with the MRA statement was “one of the most powerful conversations I have ever been a part of,” said Rabbi Jeremy Fine, senior rabbi at the conservative Temple of Aaron synagogue in St. Paul, in a post on Facebook. “It was one of the few times in my life that my head conquered my heart.”

Now, all Jewish deathbed rites, burial, and mourning rituals are online.

“The hardest part of this, is I’m so used to being by the bedside…and being there with people at the end of life,” Zimmerman said. “I’ve FaceTimed, I’ve said blessings over the phone.”

Shiva, the traditional seven days of mourning after the burial of a family member, is changing in different ways depending on the Jewish community.

Liberal denominations of Judaism are working with families to say the Mourner’s Kaddish over Zoom, and provide an online version of the mourning ritual.

“It’s kind of interesting to look at the ritual that needs to be put around the container that makes people feel safe when they’re not in the same room,” Zimmerman said. “The ritual holds people when they’re in the same room, but it needs a little bit more intentionality when you’re on these devices.”

For Jews who follow traditional Jewish law, like the local Chabad and St. Louis Park communities, Kaddish is not an option. The prayer can traditionally only be said if there are 10 men or more making a minyan, or a prayer quorum. Over the phone or Zoom, that’s not possible. The pandemic has cut them off from a lifeline of religious comfort and the expression of grief.

“It’s absolutely crushing for people,” Rabbi Borenstein, of Torah Academy, said. “People already going through a challenging time, whether it’s the Shiva or whether it’s the year of saying Kaddish, and they make tremendous sacrifices to be able to do that. And to lose that opportunity is really hard emotionally.”

Or just don’t circumcise your son? Believe it or not, his foreskin won’t hurt him. And who are you to decide his religious beliefs? He is born atheist. Leave his genitals alone!

Great opportunity to practice Brit Shalom- you can do it virtually now & again in person when the curve flattens and it’s safer to gather.

Peace instead of bloodshed

https://www.jweekly.com/2012/01/06/alternative-ritual-sans-snip-catching-on-in-bay-area/

http://www.britshalom.info/

One thing was overlooked. In Jewish law, it says “Pekuach Nefesh”, saving of a life, overrides virtually any Jewish law. If observing Jewish rituals in the normal way; will put people in a life or death situation, then according to Jewish law, it’s forbidden.

I know in the Traditional observance practice, requires a religious quorum, it is actually forbidden to do that!