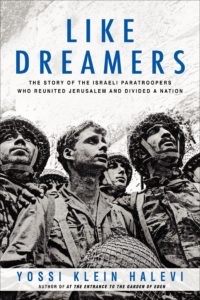

Yossi Klein Halevi’s epic: “Like Dreamers- the Story of the Israeli Paratroopers Who Reunited Jerusalem and Divided a Nation” (HarperCollins:2013)

The iconic image of the Six Day War speaks to us still. We look at the paratroopers’ awe-filled faces, gazing in wonder at the Western Wall. The euphoria of that watershed moment was felt by Jews worldwide. And yet, the astonishing victory that reunited Jerusalem created a complex reality for Israel, with issues that remain unresolved forty-six years later.

In his epic new book, Like Dreamers: The Story of the Israeli Paratroopers Who Reunited Jerusalem and Divided a Nation, acclaimed Israeli journalist and author Yossi Klein Halevi recounts the events of that victory from the perspective of seven paratroopers who fought the battle for Jerusalem.

After the war the men continued as leaders, but on very different paths, reflecting varied and competing “utopian dreams” for Israel. Peace activists, West Bank settlers, entrepreneurs, even an anti-Zionist — each one worked toward his vision of what Israel’s future should be.

Klein Halevi, senior fellow at the Shalom Hartman Institute in Jerusalem and a contributing editor for the New Republic, has written a masterpiece, a book that weaves history and storytelling into a compelling, riveting tapestry of the post-67 Israeli reality.

Temple Israel and Adath Jeshurun hosted Klein Halevi as scholar in residence at their congregations last weekend. The two congregations and JCRC hosted a breakfast for communal professionals Friday morning. TC Jewfolk caught up with Klein Halevi during the busy weekend. Below are excerpts from our conversation.

TC Jewfolk: How did writing this book affect you?

Yossi Klein Halevi: Initially I thought that this book would take me two years to write. After two years I realized that I was only beginning to understand what the book was about. I violated every deadline for eleven years. The first way that it changed me was that it forced me to go deeper than I intended to, to think about “What is our story?” It’s trying to tell the story of Israel from May 1967, until now.

One of the reasons I feel we are losing the war for our narrative is that we don’t have a narrative of the last forty-five years. We don’t really understand what happened to us. There is a right wing Jewish narrative and a left wing Jewish narrative, but we don’t have a cohesive narrative.

What I tried to do in this book is put right and left into one narrative — it’s one story. I wanted to show how young men who shared the same experiences and traumas could reach such totally opposite conclusions. My model was the four children of the Haggadah, that they are all at the table, even the evil child. I wanted to write an Israel Haggadah that would bring all four of these children into the same narrative.

What changed me deeply was being forced to enter deeply into each of their heads and souls. I had to leave aside my own opinions and treat these men as historical characters and imagine that I’m writing for Jews one hundred years from now. It was very hard to do, and one of the reasons that it took me so long. For many years I did not hear the voice of the book. Then I realized that the voice of the book is all of these competing voices. Together that cacophony forms the voice of the book, the voice of the Jewish dilemmas of this time, our struggles with ourselves. It forced me into a place of deeper empathy.

I’m hoping that this book will foster ahavat Yisrael, love for the story of Israel and love for the Jews whose ideas you find objectionable, left, right or center. Each one of our camps is coming from a place of Jewish authenticity. Ahavat Yisrael is easy when you are among like-minded Jews, and its hard when you are among Jews whose opinions you feel are threatening Jewish survival.

TCJ: How do we instill and nurture that deep bond of peoplehood when we live in such polarizing times?

YKH: The fact that you have Hanan Porat, a founder of the settlement movement, together with Avital Geva, one of the founders of Peace Now, in the same story, in the same metaphorical tent — that to me is what peoplehood means. The difference between the Diaspora experience and sovereignty in Israel is that in the Diaspora you can create your own homogenous communities and never have to interact with Jews that you don’t like. In Israel we don’t have that luxury. It’s an extended family.

The question of peoplehood is shared fate, shared experience and shared dreams.

The book is called “Like Dreamers” because it is the story of the extravagant, messianic dreams that we imposed upon this little country — the kibbutz movement, the settlement movement or Peace Now.

TCJ: Over the years I have heard you refer to the utopian dreams of the left, “We have a partner for peace” and the utopian dreams of the right, “Greater Israel”. You make it clear that those dreams are no more. Is there a dream or vision that can emerge that can guide Israel forward?

YKH: This is the first time in the history of Zionism that we don’t have a utopian avant-garde that is trying to actualize some vast dream. “Start-Up Nation” is not dream. I’m thrilled that we’ve reached this point. Israel is a much more pleasant place to live because of being a “Start-Up Nation,” but it’s not a dream that can carry the Jewish people for the next 4000 years. We need a big dream.

I’m very interested in the social protest movement that has emerged in the last few years. It was an amazing, beautiful thing, this sense of longing for the old collectivist Israel, when we were more of an overt family.

My sense is that the next big movement in Israel, and we are starting to see it emerge, will be spiritual and religious. I’m hoping that it will be the emergence of new forms of Israeli indigenous Judaism; that’s not the Judaism that we imported from the ghetto.

The grandchildren and great-grandchildren of Israel’s secular founders are increasingly looking toward Judaism for answers to spiritual questions. I sense that we are on the cusp of a spiritual transformation in Israel.

TCJ: What are the most important understandings about Israel that you want the reader to take away?

YHK: First, the vitality of the story. One of my favorite lines from the book is “He had a plan.” I didn’t realize how often I used that line, but every one of these guys is always coming up with a big plan to move Israel forward. What I like about this title, “Like Dreamers,” which comes from the Psalms, is the word “like”. These guys are all very practical, very politically-minded. They have dreams but they are also realists.

Zionism was always all about translating dreams into reality. Israel is the story of being a grown up, for taking responsibility for the messiness of history. The hard gift of Zionism was to restore to us sovereignty, power and responsibility.

My generation of American Jews fell in love with an Israel that we didn’t understand. Israel in the fifties and sixties was a very messy place. We didn’t want to know, we just idealized Israel. Now many American Jews are falling out of love with an Israel that they also don’t understand. The Israel that exists today is so rich and nuanced.

What I hope I’ve written here is a love story for grownups. My appeal to American Jews is to move from infatuation to marriage. For American Jews to move between either infatuation or disillusionment is to miss the point on both sides. This book is the summation of what I’ve learned in the last thirty years of living there. The very messiness of the story is part of what makes it so extraordinary, the courage of Israelis to engage in the hard reality we have been dealt, and that, in part, we created for ourselves.

TCJ: You have written movingly in the past of Jews as “an indigenous people returning home” and you even refer to Jews and Arabs as “fellow indigenous sons of this land”. Do you see any sign that Palestinians are ready to acknowledge that Jews are, to quote Judea Pearl, “equally indigenous” in this land?

YKH: Not yet, but the Middle East is changing. When the Arab Spring began I wrote very pessimistic articles because I felt that the West was falling all over itself in naive optimism. It was a common Israeli understanding that this will not result in an immediate victory for liberal forces in the Arab world — the most likely benefactors will be the Muslim Brotherhood. Now that everyone in the West is moving in the opposite direction — despair — now I feel that I can offer some optimism.

The Middle East is being shaken to its being, and we are going to see more and more young Arabs who want something different, who want to join the evolving, globalizing world. I’m meeting some of these people and it gives me great hope. The very fact that there are some means that the capacity for change in the Middle East has been enhanced by all this turmoil. Accepting Israel’s legitimacy is going to be an issue for the Arab world in a way that it has not been before. They will have to start debating this issue.

TCJ: What else gives you hope?

YKH:I am a religious, believing person. The story of Israel is so improbable, is so irrational, that for me, God has to be in the story in some fashion. I don’t rely on miracles — I think that is one of the lessons of Zionism — we have to initiate our own miracles. But I don’t think that we are alone in this story, and that gives me some hope.

In our lifetime we have seen miracles. I remember seeing Sadat step off a plane and Menachem Begin standing there to greet him, the first land for peace agreement being between the Egyptian leader who attacked us on Yom Kippur and was responsible for the deaths of 2600 Israelis, with Begin, the most hard-line right-wing prime minister in the early years of the State. Those two guys made peace.

It happened so abruptly — change in the Middle East does not happen incrementally. I don’t believe in a gradual peace process. This is all a fantasy. But I’m trying to keep a part of me open and ready for sudden change, for another “Sadat” who is ready to accept Israel into the region.

TCJ: If you could somehow have the ear of every American Jew between the ages of 18-35 for a few minutes, what would you say to them about Israel, about Judaism?

YKH: We are the first generation of humanity that can’t take human continuity for granted. We live in an era where we know that this human story can end. Humanity needs the wisdom of its ancient peoples, peoples that have memories that carry us through different stages of human history. The Jews are one of the very few peoples that have this continuity of memory that goes back to our ancient origins, and there is a deep wisdom of survival in the Jewish story that humanity needs.

For me, there is a deep connection between the fulfillment our great dream of redemption coming right after our worst nightmare of apocalypse: 1948 following 1945. There is something in the modern Jewish ability to turn apocalypse into a kind of redemption that humanity needs to hear, and which is not only relevant to us. We need to start understanding our story.

The other piece, and it’s related, is that it is a privilege to take responsibility for this story, because it’s one of the great stories of humanity. The Jewish story is one of the central stories that defines who we are as humanity. The world needs a good, deep and complicated Jewish people that struggles to understand its story because the whole world is listening in on us. The world is obsessed with this story.