A newly released report offers insights into the “troubling and highly complex situation on U.S. campuses at the end of the 2023-24 academic year” after Oct. 7.

The University of Minnesota is one of 60 schools with large Jewish student populations in a study by Brandeis’ Cohen Center for Modern Jewish Studies, described as “a premier center for data-driven research about Jewish life in North America” by Natan Paradise, director of the U’s Center for Jewish Studies.

Over 4,000 college students responded to the survey focused on “how non-Jewish students think about Jews and Israel and how these views relate to their other beliefs.”

Studying hate: Why and how

Leonard Saxe, one of the Brandeis researchers, explained in a podcast interview that this project about non-Jewish attitudes was inspired by research on the experience of Jewish undergraduates last year.

That study, released in December 2023, found that “a large number of Jewish students feel that there is a general climate of antisemitic hostility at their school,” which in turn negatively impacted their overall feelings of safety and belonging on campus.

The University of Wisconsin-Madison, the closest to the Twin Cities of the 51 schools studied, ranked in the top 25% of highest antisemitic hostility institutions.

Saxe said that he and his colleagues were concerned by the widespread surge in antisemitism causing some students to hide in their dorms or to conceal their Jewish identity. Even as experts, however, they didn’t know what could be done without understanding the specifics behind the hate. Consequently, the latest survey, given at the U of M and 59 other schools during the spring semester of 2024, focused on non-Jewish opinions.

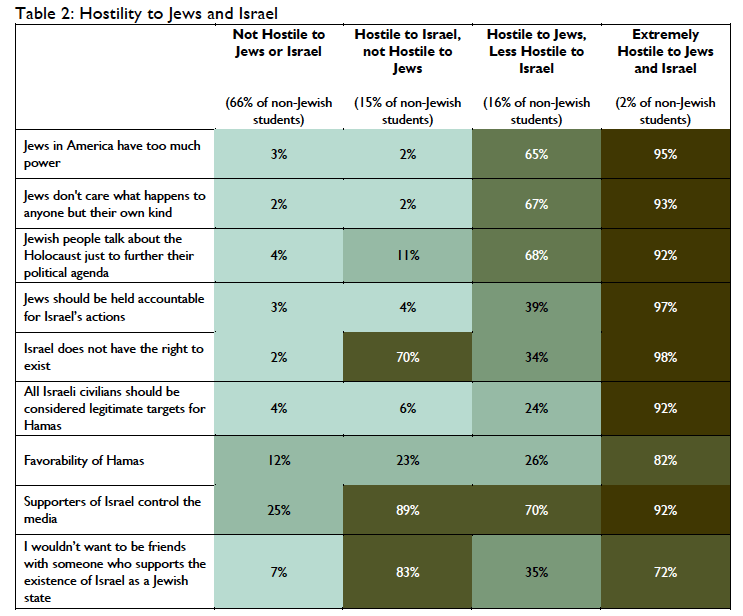

Students identified whether they agreed with antisemitic tropes like “Jews in America have too much power” and “Jewish people talk about the Holocaust just to further their political agenda.” To explore opinions about Israel, students were asked about statements such as “Israel does not have the right to exist” and “All Israeli civilians should be considered legitimate targets for Hamas.”

The researchers said they didn’t use terms like “Zionism” and “anti-Zionism” to avoid confusion over what the terms mean.

Encouraging and troubling takeaways

One key finding is that “66% of non-Jewish students did not display any hostility toward Jews or Israel and their views were not likely to threaten their relationship with their Jewish peers.”

Thirty-four percent of students, however, endorsed a pattern of antisemitic beliefs, driving campus hostility.

Saxe stated that it’s “concerning” that so many educated people in the U.S. hold antisemitic views, and added that “even a small group of people can cause a great deal of chaos.”

Of students embracing antisemitic beliefs, Brandeis categorized about half as “hostile to Jews” and the other half as “hostile to Israel.”

Table from the Brandeis University report, Antisemitism on Campus: Understanding Hostility to Jews and Israel.

“The anti-Israel hostility that is expressed – one cannot say that it is not antisemitism. In fact, it is antisemitism,” said Saxe. “In some ways, it’s a way of expressing antisemitism in the current environment that may be more socially accepted, and it may be socially [unacceptable] to express it in purely Jewish religious terms. But it’s the same thing.”

A similar percentage of both groups view Hamas favorably: 23% of those hostile to Israel and 26% of those hostile to Jews. For those characterized as hostile to Jews, 24% supported the killing of Israeli civilians, compared to “only” 6% of those hostile to Israel.

Notably, the researchers concluded that students who frame their antisemitic views as a problem with Israel “were almost exclusively found on the political left” and “these students were willing to admit that they were uninterested in being friends with anyone who believes Israel has a right to exist, a group that includes the vast majority of their Jewish peers.”

Further, “the intensity of their hostility may also be related to their higher levels of anti-hierarchical aggression, reflecting a desire for vengeance against those – including Israel and its supporters – that they see as occupying positions of power.”

This may explain why the Brandeis data from December 2023 about Jewish students reflected “greater concern about antisemitism on campus emanating from the political left than from the political right, even among those who identified as politically liberal.”

Finally, the Brandeis experts emphasized that it’s important to identify the nuances behind hate in order to tailor effective policies. They also stated that “[c]olleges have a responsibility to treat antisemitism like any other form of prejudice. This means applying existing standards and policies surrounding hate speech or harassment of Jewish students in the same manner they are applied to students in other protected racial or ethnic groups.”

Here in Minnesota

Over 6,000 miles separate the Twin Cities from Israel, but since the Oct. 7 Hamas attack on Israel, anti-Israel activists have disrupted day-to-day school functions for all students and created hostility for Jews on local college campuses.

The Brandeis research “further confirms what many of us Jews have been noting for the past year,” U student Jonathan Greenspan said. So far this year, he said “the campus is still a hotbed for antisemitic and anti-Israel activity.”

Throughout his day, Greenspan said he encounters messages of hate, such as stickers on classroom doors with calls for the destruction of Israel and its replacement by a Palestinian state, images “glorifying Hamas terrorists holding AK-47s,” and graffiti on the Union like “death to Zionists.” On the way to the bus to go to class, he passed a sticker “that read ‘Destroy Zionism,’ with a cartoon character marked with an inverted red triangle on his chest,” a symbol Hamas uses to identify targets and the Nazis used to designate political prisoners in concentration camps. To enter his on-campus apartment building, Greenspan has to pass a fellow resident’s “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free” sign.

Alex Stewart, another student at the U, said that the campus climate hasn’t changed much from last year’s antisemitism flare-up, but on the positive side, Jewish students are fortunate to have a thriving Jewish community on campus.

“I feel supported and heard by the University leadership,” she said. “We have had multiple opportunities to meet with them and they have listened to our concerns and have supported Jewish leaders!”

Stewart wasn’t surprised by the Brandeis findings. “I think it is important to know that a majority of the students at the [U] just want to go to their classes and enjoy their time on campus.” As a student, she addressed the anti-Israel versus anti-Jewish distinction. “In my experience, more often than not, anti-Israel rhetoric can turn into anti-Jewish rhetoric very quickly. This is extremely harmful and there should not be any space on campus for anti-Jewish language.”

Anti-Israel organizations are testing the U’s new resolve to enforce its rules this school year. The groups describe themselves as dedicated to human rights, justice, and democracy, but their social media and disruptive activities focus exclusively on Israel. They’re silent on humanitarian crises such as the millions of Sudanese civilians suffering what the United Nations calls “the world’s largest hunger, protection, and displacement crisis, and the Taliban’s “systemic gender discrimination and oppression of women and girls in Afghanistan.”

As the first anniversary of the Hamas Oct. 7 attack on Israel approached, one group promoted a “mass protest to honor our martyrs.” It contains no mention of the massacre and kidnapping of civilians by Hamas and states that it has been one year since “Israel began its devastating assault on Gaza.”

UMN Divest Coalition social media post about a year of “genocide” and “resistance”

“What really scares me is the physical actions they may take,” Greenspan said of the upcoming events, adding that activists called the week of Oct. 7-11 “a week of rage.”

During last summer’s state senate hearing about antisemitism at the U, then-Interim President Jeff Ettinger addressed potential violence from protestors as a consideration in the U’s appeasement approach to ending encampments, testifying that the University of Wisconsin “went the other route,” utilizing police to enforce the law, and “it resulted in injuries to numerous law enforcement professionals” as well as to bystanders and protestors.

“As for how we’re holding up, it’s difficult,” Greenspan said about life on campus for Jewish students going into a second year of relentless hostility. “But we survive, as we always do, and we find relief in the little moments, like Friday night Shabbat dinners.”

Stewart has also taken comfort in the community during the challenging times. “Minnesota Hillel has been a constant support for myself and other Jewish students in times of need. While being both a safe and secure place for students on campus, it is also a place where we can celebrate being Jewish.”

Education: the Antidote to Hate?

U professor Natan Paradise said he’s still working through his Brandeis peers’ work, but it offers “clear implications” for how the U and other institutions should respond.

“Students who are creating a hostile atmosphere on campus…cannot all be lumped into one bucket, and the responses to antisemitism – the report calls them ‘interventions’ – need to vary,” he said.

Some students openly use antisemitic rhetoric on campus. “They use [it],” said Paradise, “because the media and the internet especially is awash in it, and because of the language provided to them by various forces helping to orchestrate the protests at a national level – and some of those forces are truly antisemitic.” For some, “[i]t’s so deeply embedded in Western culture, in their churches, in the media, it’s just part of the water they swim in.”

Paradise remains hopeful about these students. “It is for these students (and faculty and staff) that I was giving seminars on antisemitism across campus last year, and I will continue to do so this year.”

What about students like the 2% categorized by Brandeis as” extremely hostile” to Jews and and who overwhelmingly support Hamas and the violent destruction of Israel?

“[T]here are the truly hateful students, and personally I don’t find it a good use of my time to try and change their behaviors, and believe me as an educator that’s hard for me to say,” Paradise said. “But [for] those students – although their speech, however hateful, is protected – when they violate campus policies including conduct code policies, the hammer of sanction needs to come down hard.”

Students Greenspan and Stewart said they have made efforts to engage productively with students who are hostile to Israel. “When Jewish student leaders have tried to have nuanced conversations and partnerships with groups that have strong feelings, we have been turned away,” said Stewart. “However, [we] have had positive experiences with individuals who are willing to have conversations about a range of topics, and that is extremely reassuring and exciting.”

Greenspan said that his attempts to engage with the organized anti-Israel movement have been rejected. “Unfortunately, there has been a normalization of what the anti-Israel crowd calls ‘anti-normalization.’” This tactic, used by extremist groups, opposes any dialogue or cooperation with Jews or Israelis who believe in Israel’s right to exist.

Prof. Paradise said his workload more than doubled after Oct. 7 and expects that it will be worse this year. “But as director I’m in the hot seat and the point person for much of this,” he stated. “And it’s important work. No one is firing missiles at me and I haven’t been chased out of my home for nearly a year, so relatively speaking I’m fine.”

Most of all, he and his colleagues at the Center for Jewish Studies remain dedicated to making a positive difference.

“Education is at the core of [our] mission,” said Paradise, “and if this past year has shown one thing clearly, it’s that there’s a lot of educating that needs to be done. So damnit, that’s what I am doing, at a time when having a Center for Jewish Studies on campus is more vital than ever.”