Bonanzaville, part of the Cass County Historical Society in Fargo, N.D., opened an exhibit called “The North Dakota Jewish Experience: Shvitzing It Out on the Prairie” last week. The exhibit is expected to be up for at least a year, and tells the unexpected history of Jewish presence within North Dakota. This exhibit, created in partnership with the Jewish Historical Society of the Upper Midwest, the Chabad Jewish Center of North Dakota, and the Jewish Community Relations Council of Minnesota and the Dakotas.

The Cass County Historical Society was contacted by Jerry Klinger, the executive director and founder of the Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation, who wanted to place a plaque that honored Jewish homesteaders in North Dakota. Klinger said that in the late 1800s

JCRC Executive Director Steve Hunegs speaks at the opening of “The North Dakota Jewish Experience: Shvitzing It Out on the Prairie.”

Photo by Kevin Taylor

and early 1900s, there was an effort for Jews to work the land.

“The idea was that because we were denied the right to own land for so long in Europe,” Klinger said. “North Dakota eventually became the fourth-largest state with Jewish agriculturists.”

Brenda Warren, the executive director of the Cass County Historical Society, said that support from the JCRC and JHSUM went beyond just helping to organize – respective executive directors of the two organizations, Steve Hunegs and Robin Doroshow – both contributed some of their own family artifacts to the exhibit.

“We had a lot of outpouring of support from the community about this component of our history,” Warren said. “We involved [Fargo’s Temple Beth El] and Rabbi Yonah Grossman (of Chabad Jewish Center of North Dakota). There’s been a lot of enthusiasm about this history.”

Hunegs said that one of the high points of the exhibition is all the agencies involved coming together.

“There were multiple perspectives and dimensions coming together to make this work,” Hunegs said.

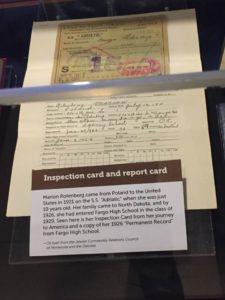

Hunegs and the JCRC contributed his grandmother’s embarkation card from the U.S.S. Adriatic, which allowed her to leave the ship with a clean bill of health, and her report card from Fargo schools.

“Immigration was critical to this family and the public schools were important to my grandma’s education,” Hunegs said. “She came here and received an incredible gift of American citizenship.”

Grossman said the current Jewish population of North Dakota is estimated at about 500, although he thinks it may be closer to 500 families.

“I think it’s great that Bonanzaville is taking an interest in the Jewish role in agriculture and economic development. It’s great for the community at large to see that commitment that is largely unmentioned.”

Kate Dietrick, the archivist at the Berman Upper Midwest Jewish Archives, explained that the established Jewish community, made up of a lot of German immigrants, didn’t know how to support the eastern European immigrants that were coming. The raised money to send them to the Dakotas, which at the time, wasn’t without appeal.

“The Homestead Act of 1862, said you could get 160 acres for free if you lived on the land and improved it for 5 years,” Dietrick said. “As a Jew in Russia, you weren’t allowed to own land. To get the land for free was appealing.”

Grossman said that there is a deep-rooted connection between the Twin Cities’ Jewish community and the homesteaders. After the homesteaders worked their land, many moved away from North Dakota to the Twin Cities.

Hunegs expressed appreciation to Bonanzaville for taking this on to help educate people about the Jewish history in North Dakota.

“Especially as we’ve seen in recent days, strengthening relationships has never been more important,” he said. “It has much of North Dakota’s and America’s Jewish history in the exhibit. Sometimes, in the same artifact.”