At four years old, my withdrawn demeanor (and, I later learned, some unsettling dark drawings) convinced my parents to bring me to a child psychiatrist. An older man with a short snow-white beard and kind eyes, he quietly observed me playing with toys on the rug of his office before assuring my parents that I would, in time, outgrow whatever was plaguing me.

He was wrong.

My school years were painful, not academically (an area where I excelled) but socially. While I wasn’t particularly teased or bullied, my fear of negative judgment from my peers was nonetheless so terrifying that I rarely spoke at all; essentially, I was invisible (at least, I did my best to become so).

As I grew into adolescence I often felt like crying; my dark moods punctuated only by fits of anger at the unfairness of it all and my evident powerlessness to transcend the bone-deep ache of despair. Looking back, I was seriously depressed, but at the time I lacked the perspective to understand that my feelings were not normal; even my parents chalked up my moodiness to typical teenage development.

Sixteen years old and miserable, I took a desperate and drastic stab at a “geographical cure” (as it’s known in some circles) for my pain – that is, blaming my unhappiness on unfavorable circumstances I clung to the hope that I could start over and leave my problems behind. I applied and was accepted to spend my final year of high school studying abroad in Italy where – after a fateful introduction to Jack & Coke – I discovered the power of alcohol to erase my anxiety and sense of isolation (at least, temporarily). It was the closest thing I knew to magic.

It would be many, many moves and many years later until I acknowledged that my problems were internal, and that no matter how far or fast I ran I could never leave myself behind.

My year in Italy marked the beginning of a bitter struggle with the co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders that would profoundly shape the next decade of my life.

In my early 20s, I spent a week traversing Israel as part of a Birthright Trip, sleeping hardly at all, chain-smoking Marlboro Reds (though in all my years of substance use before and since, I was never otherwise a regular smoker), dancing all night and going home with strangers and feeling generally irresistible, indeed, sparkling.

My adventure came to an abrupt end shortly after returning to the States when I woke up in a hospital room following an overdose of red wine and benzodiazepines (anti-anxiety medication I had been prescribed by the first psychiatrist I saw as an adult).

The doctor asked if I was trying to kill myself.

“No,” I responded, truthfully (perhaps because I hadn’t yet regained the presence of mind to lie). “I was just trying to slow down my brain.”

I was admitted to the psychiatric ward where I was diagnosed with bipolar disorder, type I. While the overdose was certainly the impetus for this event, I imagine my family history of bipolar disorder – my grandfather and uncle’s lives were also deeply affected by manic highs and severe lows, eventually treated by ECT or “shock therapy” – played a role in my diagnosis.

Fast forward again, to mid-twenties. Me in the living room of my parents’ house (where I lived at the time). My addiction had caught up with me and my parents reluctantly confronted me for stealing several hundred dollars from my father’s desk to finance my growing dependence on morphine and oxycodone. Me curled on the couch, crying, burning with shame, trying to find the words to explain this problem that ran much deeper than drugs.

Finally, in frustration I burst out, “The problem is I don’t want to live anymore.”

This was the beginning of my journey to recovery, which took me first to Hazelden (now the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation) in Center City, Minnesota and then to St. Paul (sometimes referred to in the press as “Sober City” because of its strong sober community.)

Today I am part of Minnesota’s first Recovery Corps, an AmeriCorps program that sends people with a passion for recovery into organizations providing support and services to individuals with substance use disorder.

(Here I’d like to pause for just a moment to touch on the importance of language when it comes to mental health and substance use disorders. While this could be the subject of an entire article in itself – and, in fact, has been the subject of many fabulous articles – for now I simply want to note that it is intentional and is not simply semantics. Studies have shown that the language we use informs the way we think and subsequently the way we act. For example, one study found that even professionals trained in addiction science are more likely to favor punitive treatments when a person is referred to as a “substance abuser” versus a person with a substance use disorder. And, by the way, most experts don’t consider “tough love” an evidence-based treatment — or a very effective one.)

In addition to my work in the recovery community, I also have the privilege of serving on the Mental Health Task Force at Mount Zion Temple in St. Paul. While I don’t have room here to delve into the significant overlap between mental health and substance use disorders, for me the two are deeply connected – and both deeply meaningful.

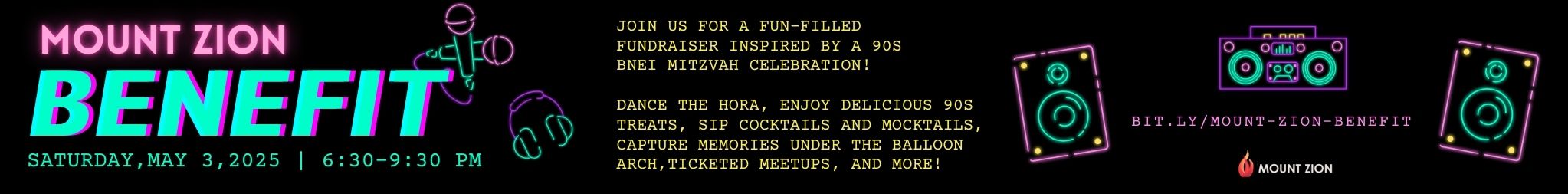

Mount Zion is the first temple I have ever joined and a foundational part of my life since I moved to St. Paul. The Mental Health Task Force stems from Mount Zion’s larger Accessibility and Inclusion work, for which the temple has received an Exemplar Congregation award from the Union for Reform Judaism and the Ruderman Family Foundation.

A huge part of the work of our Task Force has been confronting the stigma that continues to afflict those living with mental health conditions, stigma that is as damaging as it is insidious and ingrained in our cultural psyche. Much of the stigma (which also disproportionately affects certain genders and cultural groups) stems from the outdated – and patently false – notion that mental health conditions (and substance use disorders) are indicative of poor morals, bad upbringing or weakness rather than what they actually are: disorders of the brain that disrupt its normal functioning.

This month, Mount Zion is celebrating Jewish Disability Awareness and Inclusion Month with a full month of mental health-focused events including a fair for teens, a panel discussion (which I have the honor of moderating) featuring community members sharing their personal experiences with mental health and facilitated discussions of books and movies whose central characters – along with their friends and loved ones – navigate life with serious mental health conditions.

Our goal with these events is to raise awareness, encourage courageous community conversations, provide education on available resources and, perhaps most importantly for me, carry a message to anyone who still suffers in silence – the message I wish I could have heard as a frightened child, a struggling teenager and a young adult urgently searching for answers: you are not alone, and there is hope.

Sarah McVicar grew up in New Hampshire and currently lives in St. Paul.

Thank you for this powerful essay.

Thank you, Leslie, for your support! I hope we can connect soon.