On the second floor of the Turnblad Mansion at the American Swedish Institute, Beth Gendler stands before artifacts from her father. His words are inscribed on the walls. And she has a deep appreciation for what the exhibit means in the grand scheme of his life.

“My family is not supposed to be here. My children are not supposed to exist. And on my better days, that’s a real source of strength and power. On the harder days it’s ‘wow, we are an unwanted and cast-out people.’”

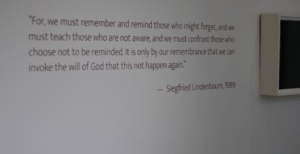

Gendler was speaking at the opening of the new exhibits at the ASI, Kindertransport — Rescuing Children on the Brink of War, and The Story is Here. The latter features Gendler’s father, Siegfried Lindenbaum z”l, Kurt Moses z”l, and Benno Black, three Jews with local ties who left their homes in Germany on Kindertransports, which moved more than 10,000 children out of Germany and Nazi-occupied countries between 1938 and 1939.

The Kindertransport exhibit was originally created by Yeshiva University Museum and the Leo Baeck Institute in 2018 for the 80th anniversary of the start of the Kindertrasnport, shortly after Kristallnacht.

“It has not been in many spots and when it originated in New York it wasn’t intended to be a traveling show,” said Susie Greenberg, the associate director of Holocaust education at the Jewish Community Relations Council of Minnesota and the Dakotas. Prior to the stop at the ASI, it had been at the Yeshiva University Center for Jewish History and the Holocaust Memorial Center in Michigan.

“We were researching ways to educate more about the Kindertransport,” Greenberg said. “This was an amazing opportunity.”

The exhibit is co-sponsored by the ASI, JCRC, and Beth El Synagogue’s Greenberg Family Fund for Holocaust Awareness.

The Kindertransport exhibit in the Osher Gallery has personal items on display, including a suitcase, a coat with a Star of David sewn into the lining, and a monogrammed tablecloth. The Kindertransports had started as a way to give Jewish children a future after Kristallnacht. Michael Simonson, the head of public outreach and an archivist at the Leo Baeck Institute, said that Jews were not allowed to attend school and were barred from most professions after Kristallnacht.

“The Holocaust, as in the genocide of European Jews, was still a few years away. And except for very few people, it wasn’t imaginable, right,” Simonson said. “But people wanted to get their children some kind of a future.”

Michael Simonson of the Leo Baeck Institute talks about the Kindertransport exhibit. He stands before a wall of tags which are facsimiles of the ones the children had as they went to their new homes. (Photo by Lonny Goldsmith)

England took the most kids — around 10,000, including Lindenbaum and Black. Sweden took closer to 500. Sweden, however, took the Kindertransport only on the condition that their parents couldn’t come to Sweden if they were able to get out.

Countries often adjusted immigration laws to allow the children on the Kindertransports to come to their countries. The U.S. didn’t, which is why there weren’t any here, and why the U.S.S. St. Louis wasn’t allowed to dock with its refugees.

“America wanted to create a Kindertransport here, but the atmosphere was so anti-immigrant and antisemitic, that it died in on the Senate floor,” Simonson said.

The exhibit captures the history of the Kindertransport from when it began to their new lives in England and Sweden. Included are the last letters that many parents sent with their children; 35-40 percent were eventually reunited, Simonson said. Parents knew which country their children were being sent to, but not where they were in that country.

“There are stories where the parents, in packing, didn’t always know what to send the children. They sent the nicest dress clothes, and then the child ended up working out a farm,” Simonson said. “German Jews were largely a middle-class community of people, they hoped their children would get an education and get into a profession.”

Upstairs, The Story Is Here was developed in partnership with the ASI, JCRC, and the three local families. Gendler pointed out a document that she believed was a naturalization document when her father became a citizen. Although born in Germany and grew up in England before coming to Minnesota, she said her father was a citizen of nowhere.

A talit created by Sandy Baron, a bowl created by her brother, and a wood-carving sign made her father are on display. (Photo by Lonny Goldsmith)

“His parents moved from Poland to Germany, so they had to have this permanent refugee status,” she explained. “He and his brother were born in Germany but because they were children of refugees, they were never citizens. And since his parents were Jews, they were never actually citizens in Poland. So it’s this eternal kind of refugee status until he became a U.S. citizen.

All three rooms were decorated with photos of the one-time-Kinders and other artifacts that were collected along the way. Sandy Baron, Moses’ daughter, had woven a talit that hung in a display with a ceramic bowl that her brother created, and wooden sign carved by Moses that read בראשית.

“It’s been an emotional journey for me and my father,” Baron said. “He was a rather private person and a lot of the material that, after he passed away in 2015, my brother and I found that we hadn’t really seen before.”

One of the centerpieces of The Story Is Here was the trunk that Black brought with him to England, and then from England to Minneapolis. It still has the original United States Lines luggage tag on it.

“It’s hard to talk about,” Black said prior to a Wednesday afternoon reception, but said that being part of an exhibit like this “is different.”

Benno Black and his wife, Annette, at the reception to open Kindertransport at the American Swedish Institute (Photo by Lonny Goldsmith)

Black was at the reception with his wife, son, daughter-in-law, and granddaughters. The items that were in his suitcase were on display around the rooms in the mansion.

“We were almost done talking to Benno when they brought up the suitcase and our mouths were on the floor,” Greenberg said. “It was really an afterthought that they were telling us about it.”

Said Erin Stromgren, ASI’s exhibition manager: “It was a time capsule. Inside the suitcase, he had some of the items that his mother packed for him when he was 13. He also had some of the items that he packed for himself when he left the UK in 1947. And he also had some pieces from his life here in Minnesota.”

The reception brought consular officials from Germany, England, Sweden, Israel, and Canada all together to help open the exhibits.

“We’re all brought together,” said JCRC Executive Director Steve Hunegs said. “And I think as [ASI CEO] Bruce [Karstadt] said quite correctly, that we apply the lessons from those days to contemporary days. And try to discern the meaning of it so we can strengthen our partnerships today.”

Said Greenberg: “[Kindertransport] is not a widely known story even for people who are well educated in Holocaust education and history. It is a piece of history that is important. It’s devastating. It’s amazing. And it’s timely, as well.”

Kindertransport — Rescuing Children on the Brink of War and The Story is Here are on display at the American Swedish Institute, 2600 Park Ave., Minneapolis, from July 22-Oct. 31, 2021. For more information, visit www.asimn.org.