Holocaust Remembrance Day, Yom HaShoah, is this Sunday. To be perfectly honest, I don’t think about the Holocaust very often.

But I am thinking about it now. I’m wondering as a third generation survivor, what can I do for people like my Grandparents who are survivors? And as a mom, what can I do for people like my children who are fourth generation survivors? I wonder about the connection between the two and where I fit into it?

My Grandmother, who I call Safta lives in Israel and has never met my husband or my children. But they know who she is from my mish-mash of memories and photos. They know that she’s a little old lady who loves to chit-chat. Kvetch. And Boss. That she has a great sense of humor, that she’s about 4’10 and that she speaks many languages. They know that she likes trashy TV, sweets and getting things done on her own. So basically, they know that she’s a lot like me.

What they don’t know about is the Holocaust. I can’t even begin to imagine how to teach my children about that horror and our family’s relationship to it. But one day they’ll need to know. Want to know. And it’ll my job to tell them. So here I am today, preparing to tell my kids about something they don’t even know to ask about yet. My Safta, Sara (Sore) Voloshin is a Holocaust survivor. And this is her story.

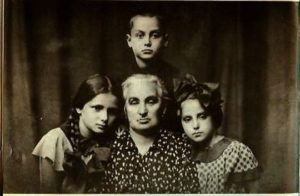

From Diary of the Vilna Ghetto. From the top: Safta's Cousin Yitzhak, My Great Aunt, My Great Grandmother and my Safta

They were led to a long line at Ponary, by a forested area. Ponary was called “the killing field” and they all knew that they were waiting to be shot. Safta’s thirteen year old cousin, Yitzhak Rudashevski had watched this scene play out for too many from that attic window and wrote about it in his diary.

They all wanted to run. Of course they did! But where-oh-where would they go? Using terrified, raw, gut instinct, Safta’s mother grabbed her arms, looked her in the eyes and told her: You’re fast. And smart. Run. Run fast. And don’t stop until you reach the other side of the forest. And while the rest of her family stood. And died. She did exactly that. She ran.

Except she got stopped by a guard, who inexplicably turned the other way and let her go.

Except she got stopped by the Gestapo, who inexplicably believed her made-up story about forgotten papers, proof of who she was and that it was okay to be out and about, and having lost her way from her work camp.

Except she was fourteen. And alone.

Except literally against all odds, Safta got taken to a work camp where Jewish police were in charge. The best of a bad situation. These policemen gave her papers to use. Papers that had once belonged to someone else; until they died. And these same policemen organized her release, her escape into the forest.

She joined a group of partisans. And at fourteen years old, she became a Holocaust-resistance “runner,” delivering weapons, papers, whatever was needed and necessary to help save lives.

After six months or so of running, working, risking and living in the forest, Liberation Day arrived. And Safta, now fifteen, rode into her once hometown of Vilna on a big bad tank driven by Abraham Sutzkever. Her partisan commander. A soldier. A poet. A writer. I so love that image of her!

“Triumphant” in this case, meant alive. Safta was triumphant. And she wanted to see her home. Her hiding spot. Where she was last within the folds of family. Again, against all odds, she went into the hiding-spot-attic and found her cousin’s diary. She read. And cried. She reminisced. And then she cried some more.

My Grandparents on vacation in 1955. My Safta is 27 years old here. What a fabulous looking couple, right?!

Safta worked. Made money. Got a law degree. In law school she met her husband, Marik. They had a daughter, my mom. Then moved to Israel. And had a son, my uncle.

And they lived. Against all odds.

My Grandparents on vacation in The 90s. She is 60-ish here and still looking great! By the way, how cute are they?!

Safta has recently decided that she wants, that she needs, her cousin’s diary to be close-by at Yad VaShem. Why now? Not sure. How? Also not sure. What can I do? Stumped again. All that I do know, all that I feel, is that my Safta has a big story to tell. And that I can do for her.

So now Safta’s story has been told. And it’s written down. Yom HaShoah is just around the corner and I haven’t discussed, taught or shared any of this with my young children. I can’t even begin to wrap my brain around what that’s going to be like, feel like. For any of us. What I do know is what it’s like to be heard. And to finally hear. From my Safta’s lips to my ears. To my heart. Which is now wide open.

We don’t have control over survivors’ fears. Nightmares. Stress. Or trauma. What we can do while survivors are with us is listen to them when they talk. Whenever that might be. And when they’re gone, we can share and pass on what we heard. Learned. Felt. That I can do.

Many of us have been told this for as long as we can remember. We must keep telling the stories. The words. The lives. Of our people so we never forget. And so they are never forgotten. And so some of the most horrid parts of history are never ever repeated. But this morning as I talked to Safta on the phone, I actually heard, actually felt that lesson. I could hear her smile in her voice once she heard that.

Well written. Your savta is very proud of you.

Mom

An extraordinary, moving story that has all our people’s history in it! As I was reading it made me remember a night I met a survivor at a seder in Canada. He started to cry, recalling how his sister wouldn’t flee the country they were in (Poland) because she was afraid they wouldn’t find kosher food. And of course, she perished. I can still see his lips trembling as he told the story.

I am so, so very grateful your savta survived, and you are telling her story.

Your grandmother sounds like a very special person. She is lucky to have you as a granddaughter, and to have you keep her story alive. My son is only two, so I’ve never thought about how I will pass the story of the Holocaust on to my children, but you’ve got me thinking. Thank you for the reminder.

What an incredible person your safta must be. Thank you for sharing her story.

Never forget. Never again.

I’ll be thinking of your safta and of so many of our loved ones when the siren sounds tomorrow.

Thank you so much ladies! So much fun to hear from all of you!

Ima– todah! *those* are perfect words!

Jenna– thank you, as always for the thoughtful comment. you always make me feel connected and heard.

& Debbie– thank you for your kind words! savta *is* that amazing! and you’re right, there’s a whole slew of topics that i’d “rather-not-discuss” with my children. might as well start gearing up together now, right?!

robin, thank you so much for the note! and for thinking of my safta during such an incredible moment. i’m honored and i know that she is, too!

What a beautifully written piece. And I love that your mom is the first commenter 🙂

phyllis, thanks so, so very much! from one ima to another, how great *is* that to have MY ima on here?! 🙂

I found you via Hadassah’s blog “In the Pink”; so glad I checked you out, and especially this particular post of yours. The Holocaust has been a framework of my life, but unfortunately, I don’t know as many specific details as you do about my father who’d survived the war in Siberia.

Let your savta be “gesundt” and continue to do the fine work she has been doing with Yad Vashem. Kol HaKavod to her and Kol Hakavod to you for sharing her story.

Will no doubt visit Minnesota Mamaleh again.

pearl, hello! thank you so much for the kind note and lovely words– both are very much appreciated. indeed, kol hakavod to *all* of us of attempt to tell our and our people’s stories. it’s the fabric of well, us! thanks also for a glimpse into your story. 🙂

That is an incredible story. My family is from Vilna, or I should say that my great-grandfather was. He came to the US in the early 1900s.

Other siblings left Vilna and ended up in places throughout the world. But we know that not all made it out. We’re in the process of trying to piece it all together.

jack, hello and thanks for the note! it is such an incredible experience to piece together the fabric of our history, for us and for our kids. i hope that all of the pieces come together for you!

Galit, this is such an important story! Thank you for sharing and please keep watching trashy television!

Marcus, hooray for 3 things– you being on here, my Safta’s story being told and *of course* trashy TV! 🙂 Thanks for the comment; it means a lot to me to hear from you on here!

thank you for sharing that story

LOZ, you’re welcome and thank *you* for reading it and for the comment! 🙂

Wow, what an incredible story. I remember having to read a lot of books and stories about the Holocaust when I was younger in Hebrew school, and visiting the museum in DC, after which I didn’t want to think about it too deeply again. So it’s been a while since I’ve read a personal story about the holocaust, and I really get your point about why we have to keep repeating these things. These stories tell you something about humanity that’s hard to put your finger on.

My family were all refugees to the US right before the war, but I’ve only met one person who was actually in a camp as a child. I only met him briefly, but the thing that struck me is that he is one of the most joyful people I’ve ever met, even now in his late 70s. It seems ironic, but maybe it’s fitting somehow.

Anyway thank you for sharing this story!

kat, hi! excellent to hear from you. i hear you completely on the ebb and flow of holocaust information take-in. it’s heart-wrenching and hard (but necessary) to learn about as a child. i know many, many adults who are well educated on the holocaust but don’t seek out any more info/ experiences about it. i totally get that.

i really appreciate your insight on the joyfulness factor. i suppose an amazingly joyful spirit would last (and continue to shine) through.

It is hard to know how best to share the dark, horrific stories of our past with our sweet children. They are so young…but so were the many, many sweet children whose lives were ripped apart by hatred.

Your Safta’s story is one of strength and courage and will be a real lesson to your children. I loved seeing the pictures…especially that final one at the end of your post.

Thank you for sharing something so personal.

thanks sarah. so great to hear from you again! the word “strong” comes to mind over and over again when it comes to safta. truly a role model and a woman to look up to– hopefully for generations to come!

What a lovely tribute. And an amazing story. But as a survivor bittersweetly told my brother when he was reporting his book: “If you didn’t have an amazing story, you didn’t survive.” (This is the book, if you’re interested: http://www.amazon.com/Lost-Search-Six-Million/dp/0060542993/ref=ed_oe_p It’s an amazing read.)

Thank you for stopping by my blog!

hi jennifer! thanks much for the note. indeed, amazing and bittersweet describe all such stories. thank you also for the book recommendation! i’m excited to take a look!

Well now I know where all that talent, those awe inspiring words come from in you. While I wish things like thids never had to be retold because they never happened, this story is a testiment to the WOMEN you come from and the amazing qualties they passed down. Wow!

I read your Safta’s story and like always, pride and sorrow fill me. My own family, my mother, her sister and her parents, are from Rotterdam. They were living there when the Nazis occupied Holland.

They also did not tell us much about their personal experiences during that time; just glimpses into their life. Now my Mom is 82 years old and she is finally starting to talk. It’s all I can do to not grill her like a witness to the prosecution, and extract every nugget of memory from her.

It is a powerful story of so many human elements. Stupid hatred, great courage, compassion, fortitude, fear, apathy, helplessness, recklessness….. and we must never forget.

I was in sixth grade, in World History class, when I first heard the ridiculous notion that “the Holocaust never happened”. A boy named Lance was touting this asinine idea. It was my first encounter with the preposterousness of racism.

Bless you, Galit, when the day comes that you begin to share this with your children. I think it’s just like the other “facts of life” talk: something to be approached in increments, instead of inundating them all at once with ideas too profound for their young minds. Ideas too profound, really, even for a middle-aged woman like me.