This is a guest post by Moshe Sokolow. This article was first published on November 23, 2011 by Jewish Ideas Daily and is reprinted with permission.

In 1789, in response to a resolution offered by Congressman Elias Boudinot of New Jersey, President George Washington issued a proclamation recommending that Thursday November 26th of that year “be devoted by the people of these States to the service of that great and glorious Being who is the beneficent author of all the good that was, that is, or that will be; that we may then all unite in rendering unto Him our sincere and humble thanks for His kind care and protection of the people of this country previous to their becoming a nation.”

In New York City, Congregation Shearith Israel convened a celebration on that day at which its minister, Gershom Mendes Seixas, embraced the occasion: “As we are made equal partakers of every benefit that results from this good government; for which we cannot sufficiently adore the God of our fathers who hath manifested his care over us in this particular instance; neither can we demonstrate our sense of His benign goodness, for His favourable interposition in behalf of the inhabitants of this land.”

While the celebrations at that venerable Orthodox synagogue continue unabated to this day, other American Jewish appreciations of Thanksgiving have ranged from the skeptical to the outright antagonistic.

In an essay entitled “Is Thanksgiving Kosher?” Atlanta’s Rabbi Michael Broyde examines three rabbis’ halakhic positions on the subject: that of Yitzhak Hutner, who ruled Thanksgiving a Gentile holiday and forbade any recognition of it; that of Joseph B. Soloveitchik, who regarded it as a secular holiday and permitted its celebration (particularly by eating turkey), and that of Moshe Feinstein, who permitted turkey but prohibited any other celebration because of reservations over the recognition of even secular holidays.

Newly presented historical information, however, may swing the annual autumnal pendulum back in favor of participation in what now appears to have begun as a holiday with both a patent Jewish theme and associated rituals. In his recent book, Making Haste From Babylon, Nick Bunker reveals an item of particular significance for both Jewish observers and critics of Thanksgiving.

Fleeing from persecution in England, the Pilgrim passengers on the Mayflower brought along their principal source of religious inspiration and comfort: the Bible. One particular edition of the Bible (published in 1618) is known to have been in the possession of none other than William Bradford, who would later serve as governor of Plymouth Colony. This edition was supplemented by the Annotations of a Puritan scholar named Henry Ainsworth (1571–1622).

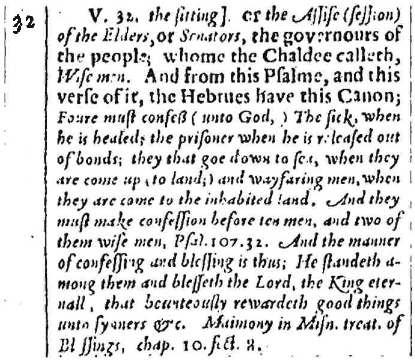

Shortly after their landfall in November 1620, Bradford led the new arrivals in thanking God for the safe journey that brought them to America by reciting verses from Psalm 107. Curiously, Ainsworth’s Annotations to verse 32 of that psalm (“And let them exalt him in the church of the people, and praise him in the sitting of the elders”) contains the following remarks:

And from this Psalme, and this verse of it, the Hebrues have this Canon; Foure must confess (unto God) The sick, when he is healed; the prisoner when he is released out of bonds; they that goe down to sea, when they are come up (to land); and wayfaring men, when they are come to the inhabited land. And they must make confession before ten men, and two of them wise men, Psal. 107. 32. And the manner of confessing and blessing is thus; He standeth among them and blesseth the Lord, the King eternal, that bounteously rewardeth good things unto sinners, etc. Maimony in Misn. Treat. Of Blessings, chap. 10, sect. 8.

If any of this looks familiar, it is because Ainsworth essentially copied over an English version of Maimonides‘ comprehensive legal code, the Mishneh Torah (in Ainsworth’s rendering, Maimony Misn.), Hilkhot Berakhot (Treat. of Blessings) 10:8, which prescribes the four conditions under which birkat ha-gomel, the blessing after being spared from mortal danger (itself derived from Psalm 107), is to be publicly recited. Citing additional verses from the psalm, Bradford compared the Pilgrims’ arrival in America to the Jews’ crossing of the Sinai Desert, corresponding to “wayfaring men, when they are come to the inhabited land”—one of the four conditions requiring “confession.”

Bunker argues, consequently, that the very first prayer the Pilgrims recited immediately upon their arrival in the New World had its origins in a distinctly Jewish practice. Accordingly, he considers this prayer service to be the original “Thanksgiving”—a service which predated, by a full year, the three days of feasting that served as the basis for the current American holiday.

Even without turkey and cranberry sauce, this vestige of Jewish influence on the religious mores of the U.S. is worth our acknowledgment and contemplation—and, of course, our thanksgiving.

Moshe Sokolow, professor of Jewish education at the Azrieli Graduate School of Yeshiva University, is the author of Studies in the Weekly Parashah Based on the Lessons of Nehama Leibowitz (2008).