Hicks is a 29-year-old Jew of Color. He is the son of a Jewish mother, who was born to a Jewish mother, who was born to a Jerusalem-born Jewish mother. Hicks is a Minneapolis native who played high school basketball at St. Thomas Academy in Mendota Heights, and college basketball at Long Island University-Brooklyn. He graduated from there in 2011 and has since bounced around the world playing professionally throughout Europe.

Hicks took the first shot at Aliyah in 2012, where he went about it on his own – and suffered for it.

“That went completely sour but I had no idea how to get started or anything,” said Hicks. “I got connected to one rabbi who wasn’t legit. I went through the Jewish Agency to get it all together, but I didn’t know I had been denied until I got on the right path.”

Hicks didn’t divulge the name of the rabbi or go more in depth. His agent, Minneapolis native Benjamin Khabie, said that may have accidentally derailed his attempt at citizenship early in the process.

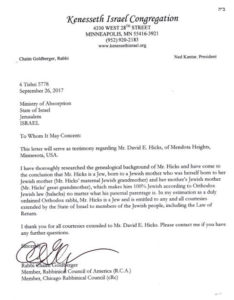

Hicks has been working closely with Kenneseth Israel’s Rabbi Emeritus Chaim Goldberger, who was connected to Hicks by Khabie, a Kenneseth Israel member. The rabbi has written letters on Hicks’s behalf that attest that he is Jewish by matrilineal descent.

Hicks has been working closely with Kenneseth Israel’s Rabbi Emeritus Chaim Goldberger, who was connected to Hicks by Khabie, a Kenneseth Israel member. The rabbi has written letters on Hicks’s behalf that attest that he is Jewish by matrilineal descent.

“He’s got all the bonafides,” said Goldberger. “There’s no technical problem. It’s just the way it works there. I don’t get surprised with the kind of things that happen with Israeli bureaucracy.”

For his part, Khabie is confused by the continued hold up.

“Usually Nefesh walks you through the process and helps you file papers,” Khabie said. “I don’t think he looks at it as ‘I’m a basketball player and they should let me in.’ But he’s genuinely interested in his Jewish background. Once you get rejected, Nefesh b’Nefesh can’t help you.”

How Law Of Return Works

“I’m trying to get (the passport) because I want to be there to play and learn about my heritage,” Hicks said. “It’s the blood in me. Why are you making it so hard?”

In 1950, the Knesset enacted the Law of Return, which declares the right of Jews to come back to Israel “as an oleh,” or someone who makes Aliyah. Subsequent amendments to the law in 1952 and 1970 hasn’t fundamentally changed it in a way that would seemingly make it harder for Hicks. However, according to Yaniv Yaron, the Aliyah manager at the Jewish Agency for Israel, there are exceptions.

“Essentially if you were born Jewish but led a Christian life, you are no longer Jewish,” Yaron said. “It doesn’t matter if you’re born Jewish. That’s my assumption in this case: Even though he’s born Jewish, he’s not raised Jewish or was raised in another faith.”

One solution would be for Hicks to convert to Judaism – although Yaron stressed that would be no guarantee of Aliyah – even though Hicks is technically Jewish. Even after conversion, Yaron said that Aliyah can’t happen immediately after.

“You have to be a member of whatever congregation in your community for more than a year after conversion,” Yaron said. “The point is, we want people making Aliyah be able to care for themselves and be part of their community.”

Yaron said that when someone applies, they need to bring a lot of documents with them, including a birth certificate, a letter from a rabbi, and their passport. Then the JAFI then as to certify the applicant is Jewish and meets the other qualifications.

“The government will take a lot of people, but if you grew up in another faith or renounced Judaism, you are no longer eligible under the Law of Return,” Yaron said. “Government tries its best for every Jew to make Israel its home. They spend a lot of money making sure people can do so and will be successful. But the burden of proof with any immigration process is on you. It has nothing to do with creed or race. If you can’t provide proof, then it’s an issue.”

The Basketball Player

Hicks is preparing for this summer’s Twin Cities Pro-Am Summer League, where he’ll be defending the MVP trophy he won last year. He likens his game to Boston Celtics’ guard Kyrie Irving – a 6-foot-1-inch point guard who can both facilitate the offense but score in bunches.

He averaged 23.3 points per game for Schwelmer Baskets in the German second division last year before hurting his knee and ending his season.

“I’m getting back to myself again,” Hicks said. “I want to spend more time with [my son]. He comes over twice per year for a few weeks at a time, but he started school so it gets harder.”

David Hicks playing for the Oettinger Rockets. (Photo by Sandro Halank, Wikimedia Commons)

Hicks was on the roster of the Iowa Wolves, the G-League minor league team owned by the Minnesota Timberwolves, on two different occasions. At the beginning of last season, he asked for his release so he could go to Germany for more playing opportunity. Given the choice between Israel and the minor leagues in the U.S., he’d pick Israel.

“I’ve done the G-League twice, and it was never a fair shake,” he said. “I didn’t have the pedigree of a top pick.”

After graduating from STA, Hicks played one year of prep school at the South Kent School in Connecticut, where he was roommates with Los Angeles Lakers guard Isaiah Thomas. That year in Connecticut gave him some visibility to bigger schools, but he had already signed his letter of intent scholarship agreement with LIU. He had been approached to transfer to Washington State University but would have had to sit a year because of the transfer and would have found himself stuck behind Klay Thompson – who has won three titles with the Golden State Warriors.

“If you’re not on the (AAU) circuit, you might not get seen,” he said. “I started every game as a freshman, and to go from that to sitting a whole season. It’s hard to be a 20-year-old kid making those decisions.

“It’s been a life-long dream to play in Israel. I’ve played in Germany four seasons, Latvia, Italy, China. I want to play in Israel until I’m done.”

Finding His Judaism

He didn’t grow up practicing Judaism – or really any religion — but always knew that he was Jewish.

“I knew I was Jewish because of my grandmother,” Hicks said. “She has her Star of David that she wears every day. My grandma said ‘you’re a black Jew;’ I said ‘I didn’t know they made those!’

Hicks is actually far from alone. According to Be’chol Lashon’s research, about 20 percent of America’s 6 million Jews are African American, Latino, Asian, Sephardic (Spanish/Portuguese descent), Mizrahi (North African/Middle Eastern descent) and mixed race.

Hicks is actually far from alone. According to Be’chol Lashon’s research, about 20 percent of America’s 6 million Jews are African American, Latino, Asian, Sephardic (Spanish/Portuguese descent), Mizrahi (North African/Middle Eastern descent) and mixed race.

Hicks’ dad is from the “country south” in Mississippi, the oldest of seven kids who moved the family up here. Hicks’ parents met when they were in high school. On his current Jewish exploration, Hicks has spent a lot of time with Goldberger’s family for holidays. He experienced his first time in a sukkah, and this year, his first Passover, documenting as much as he can with photographic evidence.

“It was a long night. I wasn’t used to that. You get a little restless after a while,” Hicks said. The rabbi wasn’t taking any shortcuts. Granted, I appreciated the experience because I had never experienced it. It took me out of my norm.”

Hicks has felt that he hasn’t been accepted as a Jew until people sit down and talk with him.

“I’m just trying to find my way,” he said. “I’ve always wanted to be more involved in the Jewish community, but I’ve never really been accepted like that, unless they sit down and see where I came from. It’s the ‘a-ha moment.’ We’re not all that different.”

Good luck on your voyage to Judaism and Israel.

Not sure if you’re reading this, David, but do you know whether your ancestry is Ashkenazi or Sephardi? If you’re interested in learning more about the Sephardic traditions, we invite you to explore the Sephardi Minyan of Minnesota (https://www.facebook.com/sephardiminyanmn/). We meet on the last Shabbat of every month for prayer services. We have Jews of all backgrounds and faith-levels that join our minyans, which are often accompanied by a traditional Sephardi kiddush. We welcome everyone who wants to pray with us and learn more about Sephardic heritage. We are not bound by hierarchy or “politics” like many other religious institutions. Please reach out if you’d like to learn more. We wish you the best of luck on your journey and in your faith.

God bless u on ur journey david.