Ever since this controversy exploded, I have struggled with what Mr. Zimmern’s comments mean and convey about perceptions of Chinese food in America and Chinese Americans themselves. As someone who is “Chewish” (Chinese and Jewish), this food controversy reminds me of the parallels between the Chinese and Jews who immigrated to this country. Sadly, Mr. Zimmern’s comments gloss over the important historical context within which Chinese-American food has risen. It is a history rife with centuries of racism, struggle, and eventually acceptance; one which is strikingly similar to that of Jews in America and in the Twin Cities. The importance of this brouhaha goes beyond Mr. Zimmern’s commentary on the food and is timely, as many Jews are thinking about what Chinese restaurant they will take out from or eat at on Christmas.

Let me start by saying I have a great deal of respect for Mr. Zimmern and his dedication and love for Chinese cuisine and its history. He has spent much of his career putting a spotlight on this food genre and its rich complexity and diversity. Perhaps his heart was in the right place, but his words did not convey that ethos. Whether this was due to editing or otherwise, he missed a great opportunity to discuss why Chinese-American cuisine exists in the first place.

Chinese food in America has been around since prior to the Civil War, and has provided an important economic role for the Chinese in America in terms of employment and ability to make a living because the Chinese were systematically and legally excluded from many occupations and subject to intense and persistent racism.

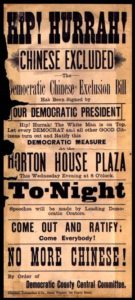

Early America was an inhospitable place for the Chinese. In the 1840s and 50s, Chinese were allowed into the country to be used as cheap labor to build the railroads. Starting with the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, many federal laws were drafted based on strong anti-Chinese sentiment following the completion of the railroad when competition for jobs increased.

A flyer inviting white people to come and ratify the Chinese Exclusion Act and suspend all immigration from China.

In the subsequent decades, laws were passed across the U.S. that banned Chinese from owning property and barred them from working in many industries (like the Jews). As a result, self-employment industries, such as laundry and restaurants, became the predominant forms of employment for the Chinese-American population. They were concentrated in Chinatowns where they could live their lives, open their businesses, and experience safety in numbers.

Because of these constraints, Chinese restaurants were places born out of necessity and opportunity. They weren’t just restaurants, but an economic livelihood for the Chinese back then and now; a way to survive and to make it in America to ensure their children had better lives than they did (like the Jews).

After the Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed in 1943, eventually Chinese restaurants sprung up outside of Chinatown and survived because they catered to their non-Chinese customer’s palate. These restaurants were forced to use American ingredients because Chinese ones were not available or very difficult to find, which meant they had to stray from traditional and authentic dishes.

It is no secret that Chinese food has been and is a part of the Jewish food pantheon. Eastern European Jews were some of the first people that frequented Chinese restaurants, back at the turn of the 19th century. Today, there are entire blogs espousing the dedication that Jews have to this particular cuisine, such as Jennifer 8. Lee’s The Fortune Cookie Chronicles.

As opportunities outside of Chinatown grew, some in the Chinese-American community were able to expand and commercialize their restaurants. Other Chinese who came over during the 20th century also had the chance to better their lives, with expanded economic opportunities and a wider array of job options, to live the American dream. An example from our own backyard is Leanne Chin, who began as a seamstress in the Twin Cities and later started a Chinese food empire that lives on today under her name.

Although I have eaten authentic Chinese food in China and in places like LA and NYC where there is a larger Chinese population demanding more authentic food, I have never felt duped by the Chinese-American restaurants I grew up eating in here in the Twin Cities. While there are numbers of them that serve what some may call inauthentic, Americanized Chinese food, there are a quite a few that serve authentic Chinese food as part of their menu or even comprising their entire menu. And some are intrinsically good, whether they are deemed authentic or Americanized.

In his apology, Mr. Zimmern said, “Here in Minnesota we have some of the most underrated Asian foods in the country all around us. Just in the Twin Cities alone, there are some spectacular Lao, Hmong, Thai, Vietnamese, Korean and Chinese foods, but a fair percentage of Midwesterners sadly ignore many of those restaurants in favor of chains whose food is simply not half as good. For many diners here the only Chinese food they know is what they see in airport fast food kiosks and malls.”

With this point, I agree with Mr. Zimmern 100%. You don’t have to go to other cities or even to China itself (though I recommend it) to experience authentic Chinese food since some of the best Chinese is here is in the Twin Cities (e.g., Shuang Cheng, Grand Szechuan, Hong Kong Noodles, Tea House, and the list goes on).

How do you know it is authentic? My gung gung (Chinese for paternal grandfather) said that if you see Chinese people in a Chinese-American restaurant then it is going to be good. Chef and food writer Martin Yan, one of the most famous promoters of Chinese cuisine worldwide, agrees with my gung gung, remarking that if you see lots of Chinese in that restaurant, you know it’s authentic.

In the end regardless of whether the food you prefer is authentic Chinese or Americanized Chinese food, there is room for both and plenty of options here in the Twin Cities for us to enjoy. Knowing the history of Chinese-American food may also shed a different light on its place in the American food pantheon.

Alene G. Sussman, is a TC Chewfolk Contributor and author of Chewishblog; self-described as “Chewish” (Chinese and Jewish), Alene grew up in Minneapolis and eats her way around the Twin Cities and the rest world as much as she can

Beautifully written . Thank for reminding us how we are all inextricably bound by the American experience.

That ‘apology’ wasn’t really much of an apology, was it? “I was wrong, but I’m also right” is not a good look. The new restaurant might be good, but Zimmern definitely has a ‘White Savior’ vibe going on.

Terrific, Alene, we both loved the article even way over here in Jaffa, the 2000+ year old suburb of Tel Aviv. We’ll be back the first of January – how about the four of us taking in some good Chinese food -Peking Garden or Andrew’s new place!

The Ingbers

Very informative article. Thank you! I’d love to see that list.

This is a great piece. Thank you for sharing this history and your personal connection Alene.

Your comments should include African Americans trials and tribulations in this same food arena. We have the same story we should all be together in this arena.

Good article understanding your history it becomes very relevant. Great

Good article, Alene! Did I tell you Elizabeth lives in Beijing? She is thoroughly enjoying the Chinese culture! She lived south of Hong Kong in Zhuhai for two years prior to moving to northern China. Peace

He’s clearly referring to a section of restaurants that produce horeshit food… Like PF changs and other fastfood type chinese cuisine.

Cut the man some slack and stop treating him like a Pariah. What a safe space bunch of garbage this is.

Looking for a poor excuse to get triggered.

While the history lesson is a good one, your focus initially on Andrew Zimmern’s comments, and a paragraph on his apology just mislead us to food that well might not “authentic” is still good. Some of your authentic you mention are not very good either. I would have like to hear more of what Zimmer had to say before we dis him for being shallow.