“I was very little when I first overheard their conversations with their friends,” said Moreimi, who now lives in Minneapolis. “Most of their friends were Holocaust survivors. I was only five, six years old, and I would be playing in the background and I would overhear some conversation, and I would become very attentive when I heard them talking about family members who perished or about their own experiences during the Holocaust. And I remember seeing sadness, pain on their faces. Tears. And I was very interested. I wanted to know more.”

The story of her parents, Ica and Ernő Kalina, is at the center of Moreimi’s Hidden Recipes: A Holocaust Memoir. It’s a diary with vivid details that deeply illustrates the care her parents showed in passing their life stories on to her daughter. Moreimi started her own book imprint, SecondGen Press, LLC, to publish the book.

“I always knew that I will write down the story for my children and grandchildren,” said Moreimi, a first-time author in her early 70s. “Initially, it was supposed to be a family history book for my family only. But because recently there is such a rise in anti-Semitism, so much hatred and prejudice and it’s very troubling. I decided that it’s very important to tell the story that if we don’t want the Holocaust to repeat itself, we must keep telling stories, we must educate others. And we must keep telling the stories and we must keep the memory of those people alive by telling their story.

“The 6 million Jews That were murdered. They had no voice. And it’s so important to be their voice. And also, I wanted to honor my parents by telling their stories. I feel that it’s an inspirational story.”

—

Moreimi said there were two things that probably saved her mother from dying at Auschwitz: Not having been married and having children and her relatively privileged upbringing in a part of Austria-Hungary which is now part of Slovakia.

Ica was in her early 30s and her sister Babi – 15 years younger than Ica – were sent to Auschwitz with their parents, who were immediately sent to the gas chambers.

“If she would have been married and have a child, women, and mothers with children went straight to the gas chambers,” said Moreimi, whose father’s first wife and child were among those murdered at Auschwitz. “She wanted to get married and have a family, but she was not interested to get married at a young age as it was the custom those times.”

From Auschwitz, Ica and her sister were sent to the Hessisch Lichtenau munitions factory. It was there

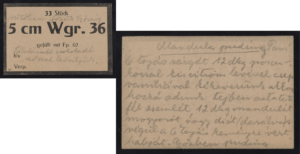

The recipe for an Almond Pudding, given to Moreimi’s mother by a woman named Pani, written on card for a 5 cm Leichter Granatwerfer 36 (lighter grenade launcher), which is a German 5 cm light mortar that saw service in early World War II.

that Ica and several others undertook an act of resistance that endures to this day.

Ica was taught German as a child and was fluent not only in that language but in Hochdeutsch, a high German dialect and she was selected to be a translator when they moved to Hessich Lichtenau. There, while on cleaning duty, Ica used that as an opportunity to take a large stack of paper from the trash and hide it while the guards were not looking. She later found a pencil, and in their barracks at the subcamp of Buchenwald, the group of women would share recipes and Ica would write them down, stashing them in a pouch in her coat – which was far too big on her malnourished frame.

The thought of food, and talking about it, kept Ica and the friends she met going.

“They actually talked about food in Auschwitz, because people were so hungry and so thirsty, dehydrated and under the hot sun on their shaved heads,” she said. “They talked about food in Auschwitz a lot.”

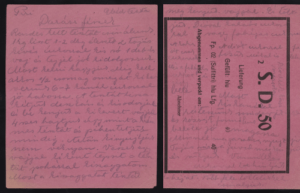

Over the course of several months, Ica wrote the recipes down. She had collected more than 600 recipes, written on slips of paper that often described what type of munitions were being made at the factory the women worked in.

The paper became something Moremi got used to seeing around the house growing up in Czechoslovakia.

“When my when my mom wanted to bake, every week we had a platter of pastries and every time she wanted to bake she would take out her recipes, these pieces of paper,” she said. “So I grew up with it was a matter of course, and then she would look through them to find them and then decide what is it she wanted to bake.”

The papers, the tie from the wood clogs that Ica wore, and a pin given to her to identify her as a translator and messenger, were all donated to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C.

Six of the recipes Ica collected made the book, and Moreimi said it was far from easy to decide which to include.

The recipe for Wasp Nest by Piri, written on a card for the SD 50 (Sprengbombe Dickwandig 50) or thick walled explosive bomb in English was a fragmentation bomb used by the Luftwaffe during World War II.

“There were so many more wonderful recipes, but I picked a few that my mom often made,” she said. “She made the Linzer and the Ischler (cookies), and not just the Chocolate Almond Tort, she made other torts.”

Translating the recipes was also not particularly easy. The recipes were all written in Hungarian, and often didn’t have exact amounts – certainly not in the way we’re used to seeing recipes written today. Recipes were recited from memory the best it could be recalled.

“It wasn’t always accurate; my mother revised many of them,” Moremi said. “For example, the tort: It’s absolutely delicious and she made so many different torts, but this one took me three times to make right because the instructions were not clear. It said ‘a tablet of chocolate.’ I said to my husband ‘What’s a tablet of chocolate in the 1920s or 1930s?’”

—

Ernő and Ica Kaufmann survived Concentration Camps, hard labor, and each survived numerous near-death experiences. Ica ran into a burning building to save the recipes, and literally fought to get her belongs back when she returned home after the war. After surviving the Nazis during the war and horrific anti-Semitism after, they later survived the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia and immigrated to Cleveland, where Erno’s sisters immigrated before them.

They both survived into their 90s, and along the way, they passed on the stories which became the book that Moremi created. What it came out of it is more than a handful of recipes; it’s a memorial to the resistance of 76 years ago.

Limited copies of Hidden Recipes: A Holocaust Memoir will be available at the Mammaleh’s Holiday Pop Up Boutique on Nov. 24 at the Sabes JCC, and on Amazon and Barnes & Noble. It will be available in wider distribution in early December at independent booksellers.

Eva’s parents were members of our synagogue, along with Eva and her husband Jack. I had the privilege to know them. They were warm, wonderful people. Their story is amazing.