In 2002, a bruising senate campaign was nearing the finish line, where incumbent DFL Sen. Paul Wellstone was running for a third term against St. Paul Mayor Norm Coleman. Wellstone, polling indicated, was going to weather the storm over his vote against U.S. use of force in Iraq in the wake of the 9/11 attacks, and win reelection.

On Oct. 25, 2002, everything changed.

Eleven days before the 2002 midterm elections, Wellstone, his wife Sheila, daughter Marcia, three campaign workers, and two pilots, were killed in a plane crash in Eveleth, Minn., causing an unfathomable political and emotional scramble in the last stretch of what had already been a long election season.

“I have such clear memories of that day and the aftermath,” said State Rep. Frank Hornstein, who was a first-time candidate for state legislature that year. “I felt a special responsibility to carry on Paul’s example. In some ways, I feel like it’s a very fresh memory. I miss him every day and think about him and what he wouldn’t be thinking and doing.”

Coleman would go on to defeat Wellstone’s replacement candidate, former Vice President Walter Mondale, in the general election. Twenty years later, how does the impact of Wellstone – as a Jew, a politician, a professor, and a person – endure?

“People continue to talk about and still invoke him and my mom and the work that they did,” said David Wellstone, one of Paul and Sheila’s sons. “It’s a testament to the good work that he did, and the leader that he was, and the leader for a lot of folks that didn’t have a voice. For me, it’s just a testament of what I already knew.”

Professor Wellstone

Rick Kahn would become Wellstone’s best friend and campaign treasurer, but he started as one of Wellstone’s students at Carleton College in Northfield, where he taught political science.

“He brought the real world into his classroom,” he said. “It was never enough to say ‘here’s the data on an issue.’ He wanted people to understand the human side, and all that meant to the lives of real people. And he wanted us to have our own opinion about what could be done about it.

“A student who profoundly disagreed with Paul could easily get an A, and get praised and encouraged by Paul, because they express their view with conviction.”

Jeff Blodgett, who was Wellstone’s campaign director starting in 1990 and another former student, said that Wellstone’s classes were often very robust discussions.

“He was big into the Socratic method,” Blodgett said. “And he would expect you to come into class to defend your viewpoint, defend your opinion, and make the case.

“The main thing he pushed his students to do, and he would say this a lot, is, ‘You need to figure out what you believe … and if you want to live a rich life, then go out and work for what you believe in.’”

Dan Cramer, another former student who grew up politically active in the Hyde Park area of Chicago, said that it was Wellstone who opened his eyes to the ways you could drive social change in the country.

“Elections are one way you drive change, but you also need grassroots and community organizing,” Cramer said. “You need broader social movements, you need effective policy, and then all of these things come together.”

Cramer, who would go on to be one of the first handful of employees on the 1990 Senate campaign, said that another Wellstone maxim spoke to him as a young person: ‘You can’t separate the life that you live from the words that you speak.’

Kahn won an award at graduation for the community service work he had done – directly as a result of Wellstone’s efforts as a professor.

“The school was affirming the value of that work, which I really appreciated,” he said. But “the next year after I graduated and citing that same work, the school tried to fire Paul Wellstone.”

Kahn said the controversy of the attempted firing led to a massive, organized protest from the students. College leadership reversed course and gave Wellstone tenure.

An inauspicious start

While many remember Wellstone’s viral-for-1990 television ads and trips around the state in a green school bus during his Senate run, his first campaign wasn’t a successful one: Wellstone ran for state auditor in 1982, losing to future Minnesota Gov. Arne Carlson.

State Rep. Frank Hornstein first met Wellstone in 1982, when he worked as an organizer for Minnesota COACT. Wellstone, then at Carleton, had several former students working there.

“He told us … ‘it’s a pathway to express progressive principles and have a statewide platform to do it,” Hornstein said. “I will sit on the State Board of Investment, and I can have a role in say, divesting from South Africa and creating other economic justice policies.’”

Standing up for progressive principles predates Wellstone’s foray into politics. Marcia Avner, led the Minnesota Public Interest Research Group, a student-directed organization that empowers and trains students and engages the community to take collective action in the public interest throughout the state, from 1977-1983, and Wellstone was the faculty adviser for its Carleton chapter. Then-Gov. Rudy Perpich had refused to meet with farmers in Minnesota who were concerned that a new DC power line was going across the state, which they believed was causing damage to their children and livestock.

“[The farmers] wanted Perpich to convene a health court to examine this but he wouldn’t meet with him,” Avner said. “So Paul and I cooked up an action.”

At a student gathering for MPIRG at Mankato State where Perpich was going to be giving a keynote address, Avner said people kept wondering why she was looking out the window when the conference was underway.

“Suddenly, they came,” she said, tearing up. “It was a caravan of farmers on their tractors led by Paul, and they encircled the building where we were with the governor. And we got to health courts.”

Wellstone’s Judaism

In 1982 at the DFL Convention in Duluth, Kahn said that Wellstone did exceptionally well in attracting Iron Range voters.

“These were hard-working people, none of whom had a particularly easy life, who saw somebody in Paul Wellstone who was a warrior on their behalf,” Kahn said. “He’s going to show up and he’s going to fight and he’s going to do it himself.”

Part of that connection, Kahn believed, was Wellstone’s Jewish upbringing.

“He would always introduce himself as somebody who’s Jewish and the son of Jewish immigrants,” Kahn said. “He never clouded that aspect of his life. It was not an identifying credential that was going to help in [the Iron Range].”

Wellstone’s father left Ukraine and his mother was the daughter of immigrants who left Ukraine due to antisemitism.

“He was always anchored in where he came from,” Cramer said. “When you’re talking about grassroots organizing, you’re talking about engaging the community. I don’t think you can disconnect those things from his heritage.”

Blodgett said that Wellstone’s Judaism manifests itself in an Albert Einstein quote that Wellstone had framed in his home: “The pursuit of knowledge for its own sake, an almost fanatical love of justice, and the desire for personal independence – these are features of the Jewish tradition which make me thank my lucky stars that I belong to it.”

“He would quote that out often kind of as to talk about what he draws from, and what he’s passionate about,” Blodgett said.

Sam and Sylvia Kaplan, longtime supporters of Democratic politicians, helped lead Jewish community pushback against the assertion that Wellstone wasn’t Jewish enough because his wife, Sheila, wasn’t Jewish, or because the Wellstone family didn’t belong to a synagogue.

“Early on, members of the Jewish community were attacking Paul for being a candidate,” Sylvia Kaplan said. “And we got together a whole group of Jews, who then put a letter in the American Jewish World defending him.”

Sam Kaplan said: “That letter led to the Boschwitz letter, because [Boschwitz] was losing support in the Jewish community.”

‘The Jewish Letter’

Blodgett got a job at Minnesota COACT, and then went to work for Wellstone, running the first part of his campaign in 1990, and then running the state office. But first, they were on opposite sides of a Democratic primary in the 1988 presidential race. Blodgett was the state director for Michael Dukakis, while Wellstone was the state chairman for the Rev. Jesse Jackson.

“Jackson was running a bold, progressive campaign – exactly the kind of campaign that Paul likes, primarily, because it was kind of pushing the debate and pushing the issues,” Blodgett said. “I think Paul knew full well that Jackson probably wasn’t going to get the nomination, but he felt it was an important thing to have his voice in the very large field of candidates that were running for president.”

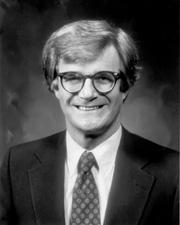

Sen. Rudy Boschwitz (Photo courtesy U.S. Senate Historical Office).

Supporting Jackson turned out to be one of the planks of what became known as “The Jewish Letter,” an open letter to Minnesota’s Jewish community – written by two supporters of Sen. Rudy Boschwitz, signed by 70 others, printed on campaign stationery, and mailed at campaign expense on Nov. 1 – five days from Election Day.

″Wellstone has no connection with the Jewish community or our communal life,″ the letter said. ″His children were brought up as non-Jews.″

The letter pointed out Wellstone’s support of Jackson in 1988, and went on to say: ″Jesse Jackson has embraced, literally and figuratively, [Palestinian leader] Yasser Arafat, and has never repudiated that embrace,″ while Wellstone never backed away from any of Jackson’s policies.

A few days after the election, Wellstone and Boschwitz each contended that the letter made no difference in the outcome of the election.

“They were both wrong,” Sam Kaplan said.

Said Sylvia Kaplan: “It was an absolute mistake by the Boschwitz campaign. We immediately called the media and we got at least one rabbi (Temple of Aaron’s Bernard Raskas) to stand up to defend Paul. There were lots of Jews who defended Paul.”

Reports at the time confirmed that signers had agreed to support a pro-Boschwitz letter, but didn’t know that it would target Wellstone’s Jewish credentials leading many to disavow the letter.

Controversial votes

Wellstone is probably most remembered for his final vote in the Senate, where he became the only senator on the ballot that year running for re-election to vote against the use-of-force resolution against Iraq in October 2002. He ended his floor speech explaining the vote by thanking his staff “for never trying one time to influence me to make any other decision than what I honestly and truthfully believe is right.”

The final vote bookended one of his first votes, another no vote on the use of force resolution against Iraq, in 1991, after the invasion of Kuwait.

“He was right on the first vote – possibly – but it a fairly popular operation that was happening so that that vote in some ways was more controversial than the 2002 vote,” Blodgett said. “Both of them were super tough to take and they both kind of bucked public opinion and definitely [put] a lot of political pressure on him to kind of go along with this so we could get back to the issues that he was strong on.”

Said Kahn: “Some notable Democrats who knew better voted for it anyway, because they thought that was the politically wise choice. The professional Democratic national consulting class said ‘it’s political suicide if you vote against it.’ There was no way he was going to vote for it. No way at all.”

Enduring legacy

Cramer got childhood friend Robert Richman to come to Minnesota to work on the 1990 campaign after working on Chicago and Illinois campaigns.

“I could either keep working in Illinois politics or have this opportunity to come in and work for Paul at a time that I thought of him as a liberal Jew in Minnesota that had no chance in hell of actually winning,” he said. “I had just gone through an incredibly cynical experience and life lesson in just the sort of brutality of pure power politics of Illinois and Chicago. To come from that environment, and to be able to just be part of something that was about trying to say something and do something and show that people could actually have an impact on politics that, for him, wasn’t about him.”

In 1999, Cramer and Richman stayed in Minnesota and started Grassroots Solutions, a consulting firm that focused on grassroots engagement in campaigns that are “committed to building healthy, just and equitable communities.”

Many of the people who knew Wellstone best continue to use his inspiration to further his message.

Blodgett was motivated to create Wellstone Action as a way, in part, to gain some clarity after the plane crash and Mondale’s loss.

“[What] was really hard about those final days, and then weeks afterward, is all these different kinds of losses that we had,” he said. “The fundamental loss of life, the loss of the election we were going to win due to factors we had no control over, which is sort of the worst feeling in the world.”

Wellstone Action, now called re:power was founded as a program to train community organizers, student activists, campaign staff, progressive candidates, and elected officials. Blodgett said that Wellstone thought one of his highest purposes was to develop other leaders.

“It was to honor and carry on Paul and Sheila’s legacy by training other people to step forward into public life,” Blodgett said. “He liked being in front of crowds and being in the spotlight, but he also really loved to honor other people and lift up other people who are emerging as leaders in their own right.”

After the reelection of President George W. Bush in 2004, Blodgett said that they had an “epic” Camp Wellstone – the weekend-long training of how to be a candidate and run for office.

“We had a whole ton of candidates, including Tim Walz. And you could tell at the time, he really had that kind of extra ‘it’ factor as a candidate,’ Blodgett said of Walz, now Minnesota’s governor but at the time was preparing to run for Congress. “And [Lt. Gov.] Peggy [Flanagan] was one of the trainers in the candidate track and helped him work on his stump speech and other things.”

Prior to working to train candidates, Flanagan worked on Wellstone’s senate campaigns.

“Walking by the Wellstone for Senate office my senior year of college changed the entire trajectory of my life. I would not be where I am today if not for Senator Paul Wellstone and his vision for Minnesota,” Flanagan said in a statement. “Twenty years after his death, the loss of Paul is still deeply felt. I feel a deep sense of gratitude and responsibility to be one small part of his legacy. I miss him every day.”

This year, David Wellstone, Rick Kahn, and others worked to rebuild the Wellstone Memorial and Historical Site in Eveleth, where the plane crashed. It features decorative memorial boulders along with plaques that tell the story of Sen. Wellstone’s political legacy and devotion to northern Minnesota.

“It was important to do something so that people would continue to always remember,” David Wellstone said of the new signs around the area, and the drone flyover and website that was created. “Twenty [years] spurred some work in just wanting to button up some stuff because people are focused on it. But every day, the loss is there for me, whether it’s one year or 20 years.”

State Rep. Frank Hornstein dedicated his get-out-the-vote push that took place on Saturday, Oct. 22, in Wellstone’s memory.

“He would want us to do politics the Wellstone way: He would want us to knock on doors, he would want us to build relationships and communities, he would want us to get on the phone,” Hornstein said. “He would want us to create community.”

Rabbi Zimmerman helped organized a memorial service on the steps of the capitol building on the evening of the crash, presided over the funeral with Rabbi David Saperstein of the Reform movement’s Religious Action Center, and spoke on behalf of Minnesota clergy at an Oct. 29 memorial event at Williams Arena on the University of Minnesota campus.

“At this sacred moment, we turn our thoughts to our loved ones who have now gone from life,” she said at that campus service. “We recall the joy of their companionship, we feel the pain of our loss. We know the tears that have filled our eyes. But we also know that our dear ones will never truly leave us as long as they are in our hearts and in our thoughts. By love are they remembered, and in memory, they live.”

Thank you for preparing and publishing this memorial, which provides inspiration at a time when we so badly need it.