Over the past decade, across the United States, college campuses have ingrained a deep sense of fear in the Jewish community.

Jewish college students have been ostracized, refused letters of recommendation by professors, boycotted, shouted down, and compared to white supremacists and Nazis – a trend largely tied to the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement against Israel. And seemingly, not a semester goes by without swastikas being graffitied on campuses, or someone posting neo-Nazi flyers targeting Jews.

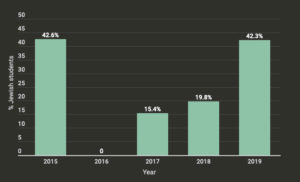

For the past few years, the University of Minnesota has been no stranger to these kinds of anti-Semitic acts. So it makes sense that in 2018, only 20 percent of UMN Jewish students said that the Jewish community was respected on campus, according to Student Experience in the Research University (SERU) survey results presented to the Board of Regents in October.

There’s just one problem: UMN Jewish students and campus professionals aren’t sure the survey results are accurate.

“I don’t think that really lines up with my experiences in the Jewish community,” said Meredith Gingold, vice president of the Jewish Law Students Association. “I can’t remember any conversations with anybody saying they don’t feel respected.”

A closer look at the SERU survey, and the confusion it causes, highlights a story more complicated than the common “Jewish students are under attack on campus” narrative. In fact, it may be that fear made the Jewish community forget that – overwhelmingly – Jewish students are doing just fine.

The Survey

The SERU survey was created in 2002 to study students’ experiences in the University of California educational system, and it eventually spread, in 2008, to other research universities. Survey data is collected from and shared with the 20 universities in the SERU Consortium, of which the University of Minnesota is a member, and can focus on diverse issues like tuition, civic engagement, and student retention.

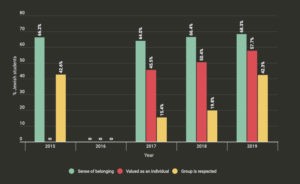

The survey researches campus climate by asking students three questions: If they feel an overall sense of belonging, if they feel valued as an individual, and if their group (be it religious, ethnic, or any other identity) is respected. Students can answer that they “strongly disagree,” “disagree,” or “somewhat disagree,” with the same variation of responses available for the “agree” answers.

The results presented to the Board of Regents in October included students’ combined “agree” and “strongly agree” answers to the campus climate questions for 2015, 2017, 2018, and 2019. (There was no SERU survey in 2016.)

While it’s true that just 20 percent of Jewish students agreed or strongly agreed that their group was respected in 2018, the year-to-year trend shows a bigger picture. According to the Board of Regents’ report, in 2015, more than 40 percent of Jewish students agreed or strongly agreed that their group was respected, which dropped below 20 percent in both 2017 and 2018 – and then rose back up to more than 40 percent in 2019.

So why the change in students thinking that the Jewish community is respected?

“For those that don’t believe in coincidence, it is very telling that the dips happen to be around the same moments in time when groups on campus have targeted and singled out Israel,” said Benjie Kaplan, the executive director of Minnesota Hillel, in an email interview.

In the spring of 2016 and 2018, BDS campaigns polarized campus with a demand for the University of Minnesota to divest from, and boycott, Israel. In the more recent instance, a student government BDS referendum passed by a slim margin, but was ignored by the university’s administration. The SERU survey happens to be administered to students in the spring.

Gingold noted that anti-Semitism has increased across the country, which can also affect how Jewish students view their community’s welcome on campus.

“Obviously BDS can be seen as an attack on Israel and Judaism specifically,” she said, “but then…there have been various anti-Semitic things across the country and on campus, so probably a combination of factors” led to the change in survey answers.

Another factor may be President Donald Trump, who was inaugurated in January 2017 after running an election campaign that many saw as vilifying minorities and immigrants. Anecdotal evidence and several nationwide surveys show that minorities like the LGBTQ, Muslim, and Latino population felt more unsafe after Trump took office.

In the SERU survey, Hindu, Jewish, and Muslim students all reported a significant drop in feeling like they were respected on campus in 2017.

Rabbi Yitzi Steiner, co-director of Chabad on campus, agreed that the Trump era may have affected Jewish students’ answers.

“In general people felt and feel unsettled,” he said, “and that’s my only guess of why those numbers dropped.”

Despite the cautious theories on why Jewish student felt less respected in 2017 and 2018, there were no answers as to why students felt more respected in 2019. And curiously, at the same time that “group is respected” answers fluctuated, Jewish students had some of the highest rates of feeling a sense of belonging, and being valued as an individual, compared to other religious groups on campus.

For some, that’s not so surprising.

“I think that’s completely accurate,” said Chava Bouchard, president of the Chabad student board. “As an individual, I feel like people think it’s cool I’m Jewish. But from the group perspective, people look down on Jewish people, look down on Jewish activities, and are disrespectful towards it as a whole.

“It’s much easier to be anti-Semitic when you are going against the entire group than individual people, because you realize they’re people, and it’s hard to stereotype individuals versus the group.”

The strong sense of belonging and individual value may also reflect the the campus Jewish community more so than campus as a whole. “It’s natural for Jews to find community with other Jews on campus,” Gingold said. “The idea of belonging has always been strong in the Jewish community because of the strong Jewish organizations that are on campus.”

Though the SERU results seem to point to real trends on campus, when asked if the low responses to “group is respected” in 2017 and 2018 reflected actual student attitudes, everyone interviewed for this story said no.

“It doesn’t make sense to me,” Steiner said. “Absolutely” the Jewish community on campus is respected, he said.

A Disconnect In The Community

No one is sure about what to understand about Jewish students on campus in light of the SERU results. But regardless of statistics, the experience of students and campus professionals points to the kids being all right.

“I think most young adult Jewish kids at the University of Minnesota are living their life,” Bouchard said. “They like the Jewish culture, they like the vibes…but I don’t think, on most days, they go thinking about anti-Semitism on campus and the campus climate. Overall, campus is doing pretty okay.”

If anything, the broader Jewish community’s fear of anti-Semitism on college campuses, or the idea that campus is a “battlefield” for Jewish students when it comes to Israel, is somewhat overblown.

“It’s more of a concern for incoming freshman, parents, and community members,” Steiner said. “In my opinion, it’s a non-issue. The idea of students feeling targeted, and anti-Semitic incidents happening, has thank God gone down so much that it’s just not something that students are thinking about or worried about.”

There are no official figures for anti-Semitic incidents at the University of Minnesota, but Steiner’s impression is that, even as anti-Semitism may be rising in the world at large, it is largely absent on campus. According to him, many people are still worried about anti-Semitism on campus because Jewish organizations over-publicize anti-Semitic acts to aid in fundraising.

“When there’s anti-Semitism, it’s very easy to go ahead and raise money, and it’s very easy for organizations to validate and legitimize their cause,” Steiner said. “Unfortunately, when doing things like that, when exaggerating or exacerbating incidences, not only does it fear monger, but it’s actually very detrimental in the long run.”

Jewish parents and potential freshmen can easily get the impression that the University of Minnesota is not safe for Jews, Steiner said, which makes it challenging to bring more Jewish students to campus. “It ends up…chasing them away,” he said.

Of course, there are still some challenges for the Jewish community on campus.

Students have a difficult time balancing Jewish holidays with the university’s calendar, and sometimes professors won’t accommodate missing class for religious reasons. The university has also been criticized at times for a lack of transparency when disclosing or acknowledging anti-Semitic incidents on campus.

Other issues affect Jewish students, but not because of their Judaism. “When I think about feeling safe on campus, it’s more about the fact that I’m a woman walking alone at night,” Gingold said, “versus the fact that I’m Jewish and I think someone is going to come after me for that identity.”

And though Jewish students aren’t really focused on campus anti-Semitism or how respected they feel as Jews on campus, “there ARE daily, weekly, and monthly occurrences of anti-Semitism and anti-Israel bias on campus that activate all of our inner defense mechanisms,” said Kaplan.

“For the most part I believe Jewish students, as individuals, feel welcomed and respected at the U,” Kaplan said. “Hillel, Chabad, Jewish Studies and Greek life offers tremendous outlets for Jewish learning and expression, and are much more robust outlets than most groups on campus have.

“However, in times when Jewish values, history, or community are attacked (be it a swastika on a dorm room door, or an all campus referendum singling out Israel for condemnation), we tend to feel the impact collectively.”