Diego” wanted to start his own business for the same reason many do; to help his family have a better life. He was working in his native Honduras at a company that sold meat when “Rebecca,” Diego’s wife, suggested he take out a loan and start his own business, which Diego did with his brothers in February 2012.

As the business became successful, Diego ran across a problem that was common in Latin American countries.

“There is extortion, corruption and bribery, and we had to pay ‘protection’ to the gangs,” Diego said, through a translator. “We were working there, living a pretty middle-of-the-road life, trying to get a better education for our kids.”

The problem in Honduras with a successful, growing business is that it means a larger cut going to the warlords and gangs.

“As the business was getting better, we were getting intimidated more,” Diego said. “We were surrounded on all sides of this.”

In August 2013, it became too much for Diego’s oldest brother.

“He was getting uncomfortable because they are experts in making people uncomfortable,” Diego said. “We had to pay more often and larger amounts as the business grew.”

He pauses.

“It’s hard to talk about. It brings up a lot of feelings.”

Diego and Rebecca’s refugee journey to the United States started eight years ago when he was sent photos of his murdered brothers after years of extortion. It has ended with a family of seven moving into their own residence in Minnesota. But for exactly 37 months — they lived in the basement of Shir Tikvah Congregation in Minneapolis.

Diego and Rebecca (not their real names) and their five children — the youngest is 2-and-a-half and Shir Tikvah’s basement had been the only home he’s known — have been able to freely leave the synagogue for their own residence because they received a stay of deportation, a one-year reprieve while they wait for some permanent resolution that allows them to stay in the United States. But until that letter came, leaving the shul was a risk.

The family ended up at Shir Tikvah because the South Minneapolis reform congregation declared it would be a sanctuary congregation — that it would temporarily shelter people who were seeking asylum in the United States. The movement of houses of worship housing asylum-seekers isn’t new; it dates back to the 80s as American foreign policy contributed to havoc in Central America.

In the Twin Cities, the movement in its current iteration ramped up in mid-November of 2016, when representatives of more than 200 churches, synagogues, and mosques braved an ice storm to come to an informational meeting. The ISAIAH Network, a multi-racial, state-wide, nonpartisan coalition of faith communities fighting for racial and economic justice in Minnesota, became the point organization for the sanctuary movement in Minnesota.

“The day after the 2016 election our staff came together because we were concerned with the policies that this new president[-elect] was projecting,” said Minister JaNaé Bates, the director of communications for ISAIAH. “We knew that we had a series of congregations involved in immigration work, but what about the idea of sanctuary extending to places of worship?

“We didn’t know what we were doing. But (we thought) let’s be in community and figure it out together.”

Through the corruption and extortion, Diego had another issue weighing on him: he was keeping it a secret from Rebecca. But what Diego didn’t know was that his brother was starting to have an increasingly difficult time coping with the situation as more and more money was demanded of them.

“My oldest brother was uncomfortable keeping the secret, and the people extorting could see the business was growing — just not how much,” said Diego. “They had other conditions and were very threatening and strong-arming him at this point.”

Said Rebecca: “[The brothers] asked for help from the police because they were frustrated and didn’t know what to do.”

Despite moving to another area of the country, trouble followed. Running away within Honduras became an impossible endeavor, and extortionists kept trying to get more and more money as the business continued to be successful.

Diego said his older brother was going to do an interview with a local newspaper and get the story out, only for the extortionists to find out.

“They found out about it right away,” Diego said. “They came in three trucks, they were armed, and they took him in the truck. They said: ‘We know! The police work for us.’”

“[My brothers] were trying to get us freed,” Diego said. “[The gang] found out and [my brothers] got killed for it.”

Diego’s oldest brother had a passport and visa to come to the United States on a Monday. They went to the morgue to identify him two days before he was to leave.

Sanctuary As A Jewish Value

The Rev. John Fife remembers when he was told by someone who worked in legal aide that smuggling refugees into the United States to protect them was necessary; otherwise, they’d be sent back to a dangerous home.

Fife, now the pastor emeritus of Southside Presbyterian Church in the “oldest, poorest barrio of Tucson, Ariz.,” is known as the founder of the modern Sanctuary Movement. In the mid-1980s, his church publicly declared itself a sanctuary, the first in the country. Fife invited his friend Rabbi Joseph Weizenbaum z”l of Tucson’s Temple Emanu-El, to speak at an interfaith service to make that proclamation official.

“Joe said, ‘Thirty-seven times it says in the Bible to welcome the alien because God didn’t think we’d get that right,” Fife recalled.

Fast forward 31 years, and Weizenbaum’s proclamation then is exactly why Shir Tikvah made its declaration now.

The concept of being a sanctuary shul, to Shir Tikvah’s Rabbi Michael Latz, comes back to one of the central tenets of the Torah that Weizenbaum shared.

“Of the things in my mind that is clear, according to Torah — so the history of the Jewish people and the founding of Jews — is radical hospitality, hacnisat orchim, welcoming the stranger,” he said. “The very first story of Abraham and Sarah in the Torah, as he’s recovering from his [circumcision], they rush out to greet the strangers to welcome them into their tent with food and drink. They don’t ask their names. They don’t ask for paperwork. They don’t ask for their documents. They just welcome them. And that’s the core narrative of who we are as a people.”

So the decision was made; but what did it mean for the building? As one of the smallest synagogue buildings in the Twin Cities, it’s not like the facility was full of extra space to spare.

“We declared and then tried to figure out what it meant,” Latz said. “People living in sanctuary are not hostages; they are free agents to come and go as they please. Our job is to do our best to keep them fed, housed, and safe. But safety and sanctuary does not come from a building being a fortress — though that helps. Safety comes because we’re making a moral claim. We’re drawing a line in the sand to say our religious values trump the desires or the whims of any particular Justice Department and that we are standing up to them.”

Rebecca says some of the details are hard for her husband to remember. The cold room at the morgue wasn’t working so the bodies were tossed aside like trash.

“I wouldn’t wish that for anyone,” she said.

This is what started Diego’s journey to the U.S., while Rebecca isolated herself and the children in an area of Honduras with no cellular service. They were afraid of deportation from the U.S. if they tried to go, and they were also worried about what was going to happen at the airport if they tried to leave.

“We were afraid of the airport security because everyone works for [the gangs],” Rebecca said. “Everyone works together in like a net or chain, and so if one of the people at the airport finds out, they’ll kill you outside the airport. What are we going to do? How do we make sure we’re not found?”

Diego had only one goal when he left Honduras.

“Our goal was to survive. We wanted to go somewhere safe,” Diego said. “We didn’t have a lot of resources so I came here alone. We wanted to just live.”

Diego’s aunt had worked on a farm in Minnesota, and she assisted him in getting to the state, which wasn’t easy. He came through the border from Mexico into Texas and explained the situation to them. He spent four months of 2013 in a Texas detention center and was very nearly sent back home.

“I was begging not to be deported,” he said. “People were being grabbed and thrown out of the country. I knocked on a door and begged for help. I was chained, shackled, and it would have been easy to throw me out.”

Diego explained everything to a skeptical border agent who, ultimately, held Diego’s fate in his hands.

“It was like God touched his heart and saw how sincere I was,” Diego said. “They were going to take me back to Honduras and I felt like I was going to be killed.”

‘A Cathartic Value Statement’

As Latz remembers it, Shir Tikvah announced that it would become a sanctuary synagogue at the symbolic time of 11:01 a.m. on January 20, 2017 — one minute after former President Donald Trump was sworn in.

“The rhetoric, obviously, that was used by the former guy against Muslims and Mexicans and immigrants and everybody was so appalling,” Latz said.

Three of the five kids in the playroom that was available to them at Shir Tikvah. (Photo by Lonny Goldsmith)

Rabbi Arielle Lekach-Rosenberg is the staff person that leads the sanctuary effort at Shir Tikvah — and it’s a program that predates her July 2017 arrival to the synagogue.

“It came out of a real desire both to offer a clear resistance to the policies that were being brought to the fore,” she said. “And I think it was also sort of a cathartic value statement for the community: this is where we stand. This is what we’re about.

“I think all of us wish that this statement wouldn’t be necessary. And yes, I think that there was some risk in living into that statement and living into those values.”

The risk became something to worry about four months into the family’s residency at Shir Tikvah, when on Oct. 27, 2018, a man walked into the Tree of Life – Or L’Simcha Congregation in Pittsburgh and killed 11 worshipers on Shabbat morning. The alleged shooter tied his motive to the “[Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society] bringing invaders into the country,” he wrote in an online post. The synagogue had, the week before, participated in HIAS’s National Refugee Shabbat.

Three months after Diego arrived in Minnesota, he sent for Rebecca and the kids. Once they got here, navigating the system was very complicated.

“After two years of being here, we were trying to fight to stay here,” she said. “Things are still pretty bad and we’re in duress and we didn’t want to go back. We just wanted to stay here.”

Rebecca and the children got here, and they were helped by a friend who works on a farm in Hutchinson.

“It didn’t make any sense to move if at any moment we could be deported,” she said.

A friend helped the family get to Shir Tikvah in 2018. They had no idea that they’d still be there more than three years later.

“We thought [it would be] about three to five months,” Rebecca said. “Then one year passed, and another year passed. They’ve been very good to us here.”

As good as the Shir Tikvah — and extended volunteer community — has been to the family, Diego does not feel at peace. Even now, with the degree of security from having received a stay of deportation.

“We’re still being chased one way or another,” he said.

Said Rebecca: “It’s just constant stress. What happens if they say no more time? What happens to us? What happens to our kids?”

A Large Volunteer Network Steps Up

Over the course of the past three years, more than 190 people have actively volunteered to help Rebecca and Diego’s family — half are Shir Tikvah members, and half from a network of other faith communities around South Minneapolis. Lucy Marshall, who has been working as an intern at the synagogue and helping to support Lekach-Rosenberg’s social justice work, said one of her key roles is to coordinate transportation volunteers.

Listen to “Lucy Marshall” on Spreaker.

“[For example] today we had four dentist appointments, so I coordinate with volunteers that drive them from Shir Tikvah to where they want to go,” she said. “We’re careful [that] the vehicles they’re driving don’t have any violations. We need to ensure there’s not going to be a reason to get pulled over.”

Dennis Guillaume, the Shir Tikvah Sanctuary Committee co-chair, said that the work could never have been done without the support of houses of worship in the sanctuary coalition.

“There was enormous support from so many other congregations, mostly churches, who stepped up and helped financially and with volunteers,” he said. Temple Israel and Mayim Rabim are two synagogues that are working in a supporting role.

One of those congregations, the Spirit of St. Stephen’s Catholic Community, emailed Shir Tikvah to tell them that the church’s Sanctuary and Resistance Task Force will be making a $1,000 donation to the family’s GoFundMe that has been set up to help with their transition.

“Your congregation’s dedicated sanctuary work has been a gift and an inspiration to all of us!” the email said.

The shopping list that Rebecca, Diego, and family fill out each week. Volunteers do the shopping trips weekly. (Photo by Lonny Goldsmith)

Lekach-Rosenberg said the volunteers are there to support the family in everything: from celebrating birthdays and getting the kids to school, to doing grocery shopping, laundry, and — until COVID hit — sleeping on an inflatable mattress in what the family would later use as their classroom.

The volunteers also helped to confront the loneliness and despair of needing to live in isolation, particularly as a very limited number of people associated with the synagogue knew of the family’s situation. The family occasionally appeared out into the open within the shul, for which they sought Guillaume’s blessing.

“There was a Friday night where the family was sitting in the balcony in the choir loft, and we turned to face the door at the end of Adon Olam, and the family all waved,” Guillaume said. “That was my favorite. The people who knew all waved back.”

“The family would come to choir rehearsal or come to shul and hang out in the Oneg hall afterward,” Lekach-Rosenberg said. “There wasn’t a sense that this was the family that was living here; we were all treading carefully and trying to learn together what was possible to share, and what we needed to keep quiet to keep the family safe. It was a hiding-in-plain-sight sort of situation.

“Now, there’s going to be certain people who’ll say ‘Oh, so those are Arielle’s friends who came to choir practice!”

This was the second time Shir Tikvah hosted an asylum-seeker — the first was a single individual who was there for a couple of months. Latz said they had received a donation to prepare the space, which included adding a shower.

The family’s space has two bedrooms, one for the parents, and one for the children. There are three bunk beds set up with a small sitting area that the three youngest — all boys — enthusiastically show off.

So the space was ready for the family to move into. Or at least, Lekach-Rosenberg said, ready-ish.

“I had gotten a call from someone with ISAIAH trying to find a safe space for this family, and so we went over to Shir Tikvah,” she said. “They were already there. And we basically had to make a call. It housed a single person before; now it had to house six and the mama was pregnant.

“So it really was a feeling of, well, we have space. And there is a profound need. So let’s do it. But we had no idea they would be there in [July] 2021. But we couldn’t let up until there was relief. And thank God, suddenly, we’re in a place where we get to talk about it.”

In the heat of the moment, however, talking about it is the last thing that congregations are going to do.

“One might think that a community would be really proud to let the world know that they are doing this work,” said an East Coast rabbi involved with the sanctuary effort. “The reality is, especially in the last four years, it had to be under wraps for a lot of communities because there was significant risk involved. First and foremost, for the asylees. So confidentiality is key, and a lot of communities do this work quietly.”

Once the family was in, Latz said they and the volunteers set about getting them fully settled.

“We had kids in schools, we had to deal with the school system, we had health needs, we had a baby,” he said. “We had just all these teams of people figuring out what to do. And, it was a massive operation: Grocery shopping for six, now seven people, and this year had four of the five kids in different schools. It has been a lot longer than any of us thought. We were all pretty terrified.”

Even with the help of volunteers, Diego and Rebecca’s fears never go away.

“It does give us fear every time [the kids] leave,” Rebecca said. “And we told the kids not to talk to anybody [about their situation] because if anyone found out and didn’t like it, they could call the authorities and bad things could happen. And the kids at some point have asked ‘Why do we live in a different type of house than everyone else? Why can’t I talk to anybody?’”

The older two now know about the situation. The youngest, born while the family was living in Shir Tikvah, just wants a normal bath where he can blow bubbles.

“It’s been hard at times, but at the same time, we’re just so grateful to have a place to stay and to live,” Rebecca said. “It’s been hard for us, but it’s also been hard to watch our children have to always err on the side of caution even just to go to a park or on a walk. We’re having our needs met, and we feel really good about that. But at the same time, I wish we could go out more freely and not have to always look over our shoulders.

“It’s been seven years of instability. We can tough it out but I worry about our children.”

A Jewish Presence

Aside from the view of Rabbis Latz, Lekach-Rosenberg, and Weizenbaum, there has long been a Jewish presence in this fight.

“The Jewish footprint is all over the refugee and asylum system,” said Robert Aronson, the president of the board of HIAS and a Minneapolis immigration attorney who is not involved in this particular case. Aronson said the Refugee Act of 1951 is an outgrowth of the aftermath of the Holocaust, where a government was persecuting minorities. “Over time, it’s been somewhat expanded to [when a] state actor [is threatening people] or situations where the state cannot intervene, like gang violence.”

Aronson said that there are two streams of refugee resettlement into the United States: The system, in which organizations like HIAS and other faith-based groups work in a very structured program; and asylum seekers, like Rebecca, Diego, and family, which Aronson said is a much more unstructured program.

Even predating President Trump’s policies, asylum seekers would show up at the border and throw themselves at the mercy of the United States. There was then a two-step process for asylum: The seeker has to argue that they have a “credible fear” of living in their native country due to persecution and the risk of being murdered. If the criteria is met, they are allowed into the U.S. for further hearings.

If someone undocumented is living in the United States and is facing a fear of deportation, that’s when they might avail themselves of the sanctuary movement.

“It’s been a doctrine for quite a while that the government enforcement agencies, Immigration and Customs Enforcement, will not invade a house of worship to arrest and deport a foreign national,” Aronson said. “Various houses of worship have declared themselves sanctuary congregations. They’re going to be restricted to living, breathing, dying, in that location but at least it spares them of the immediate threat of deportation.”

The stay of deportation is now what spares the family the immediate threat, though it doesn’t formally change their legal status. They have some supervision requirements where they need to do check-ins.

“People can be undocumented and be here without legal documentation,” Marshall said. “That was the case with our family. You are no longer in threat of deportation, likely, because there’s been new guidance from [President Joe] Biden around whom to prioritize deportations, and it does not include people who fit the profile of our family.”

How Are Buildings Used?

As synagogues are hoping to be able to reopen, Lekach-Rosenberg said that she hopes congregations examine their spaces and how they use them.

“Why do we have buildings? If we step back, what good are these spaces to us? And how are we really using them? To be in service, right?” she said. “I think that there’s a lot of really interesting reflection to be done there.”

Lekach-Rosenberg describes the space the family was living in as a “not glorious space.”

“Let’s figure out how to use our not-glorious spaces to be able to lift up. And problem-solve when things go wrong, as they inevitably do.”

While Shir Tikvah’s religious school was running, the family was living down the hall from the classrooms. A playroom was set up in one space which is used as a children’s area during Shabbat services. A library/classroom for the family was set up in what had been a religious school classroom. The hallway to their living space was turned into a parking lot for bicycles that had been donated for the family to use.

“Shir Tikvahniks feel like the whole space is our living room. People engage with the building like it’s our hangout,” Lekach-Rosenberg said. “Just getting used to the idea that there was space that wasn’t accessible took a lot of practice.”

As a precaution, a volunteer would sit outside of the apartment during high-traffic times just to be sure someone didn’t open a door they shouldn’t.

“People were so used to saying, ‘oh, there’s a closed door. I want to see what’s behind there,’” she said. “We love that feeling that people feel so welcomed. And it wasn’t possible in these last years.”

Diego and a volunteer move a bed frame into a van that is moving his family’s belongings to their home. (Photo by Lonny Goldsmith).

For much of the last half of the family’s stay at Shir Tikvah, they were also the de facto caretakers as the synagogue was closed.

“I felt like everyone else was feeling what we were feeling, during the coronavirus,” Rebecca said. “Everyone else was stuck in their houses and we were stuck in the building. It was an interesting perspective.”

Rebecca said she hopes this is the last move.

“Uno mas; no mas,” she said. One more; no more.

She hadn’t planned what the family was going to do first when they get into their home. But keeping in touch with everyone that has helped them is a top priority.

“[We’ll] invite all the volunteers over to thank them,” she said. “We always want to maintain the connections we made with the volunteers.”

Said Diego: “[We] just [want to] make the kids happy and meet their every need. And we’ve been working and working towards that.”

Epilogue: On The Road To Their Home

On July 31, the family packed their belongings and, after 1,127 days and nights, left their home in the basement of Shir Tikvah. More than a dozen volunteers and sanctuary committee members came to see the family off, carry out bed frames, and wish them well.

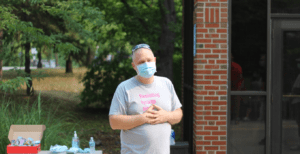

Rabbi Michael Adam Latz addresses the group of volunteers gathered at Shir Tikvah on July 31, 2021, to send the sanctuary family off. (Photo by Lonny Goldsmith).

“Today is 37 months of you living with us, and now we help you to your new home,” Latz said. “People ask why we did this. Because we needed each other. We love you and you’re always welcome back.”

Rebecca, Diego, and the two oldest children gave brief, tearful, thank yous to the group of volunteers that were there to help.

“Thank you to everyone who remembered us when we were alone,” said the oldest daughter. “Thank you for always keeping us safe.”

Said Rebecca: “I’m so grateful. I don’t have the words.”

Latz then sent them off with a blessing:

“Y’varechecha Adonai v’yish’m’recha.

May God Bless you and keep you.

Ya-er Adonai panav eilecha vichuneka.

May God’s light shine upon you, and may God be gracious to you.

Yisa Adonai panav eilecha, v’yaseim l’cha shalom.

May you feel God’s Presence within you always, and may you find peace.”

This piece received 1st Place in the category Award for Excellence in Writing About Social Justice and Humanitarian Work from the American Jewish Press Association’s 41st annual Simon Rockower Awards for Excellence in Jewish Journalism.

This piece received 1st Place in the category Award for Excellence in Writing About Social Justice and Humanitarian Work from the American Jewish Press Association’s 41st annual Simon Rockower Awards for Excellence in Jewish Journalism.