Earlier this year, Minnesota Jews felt relief as more than 20 school districts changed their Sept. 7 start dates to avoid conflicting with Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year. To many, it was a welcome sign of the Jewish community being heard and respected after decades of being sidelined by a majority-Christian environment.

But one notable educational institution didn’t move its start date, saying that a variety of scheduling issues made an adjustment too difficult: The University of Minnesota.

“We were having success after success with local school districts, making these shifts, but it didn’t seem to matter,” said Ethan Roberts, director of government affairs for the Jewish Community Relations Council of Minnesota and the Dakotas, which advocated for the school district start date changes.

The university’s decision elicited a wide range of Jewish reactions, from bewilderment and acceptance to anger and accusations of antisemitism.

When hearing from community members about the situation, the “only common theme [was] the disbelief that, in 2021, a university of our size can’t figure out (with years of notice) how to accommodate non-Christian holidays,” Benjie Kaplan, executive director of Minnesota Hillel, said in an email.

But a retroactive look at the U’s decision-making process, examined here with new reporting (Editor’s note: the reporter is a recent U graduate), raises doubts about the university’s assertion that there was no reasonable way to adjust the calendar for Rosh Hashanah. It also serves as a guide for navigating future scheduling conflicts that affect Jewish students and faculty.

“When you go to college, it’s the first time you’re responsible for your own Judaism,” said Debbie Stillman, president of Minnesota Hillel’s board of directors. “The High Holidays always come in so fast. For some kids, that’s really hard…and it can set up a pattern for the future. The feeling that they need to be in class and the pressure they feel — even if they have ‘permission’ not to be — often makes them skip out on services.”

“And I don’t want students to have to choose between their Judaism and their education.”

Advance Notice

In October 2018, it was already clear that the U’s fall 2021 start date would be a problem. So Kaplan and then-Minnesota Hillel Rabbi Ryan Dulkin contacted the university administration through Michael Goh, vice president at the Office of Equity and Diversity.

“We were told at that meeting, ‘thank you for bringing this to our attention, we will look into it,’” Kaplan said. He thought the U would work on resolving the conflict with Rosh Hashanah, but nothing changed.

When asked via email why the university didn’t address the start date issue in 2018, Goh deferred to a statement saying, “we have valued the advocacy and partnership of Hillel staff and Jewish community members…and look forward to continuing our shared efforts to ensure that Jewish students, along with all of their peers, can find success in their academic journey here at the University of Minnesota.”

In fall 2020, Kaplan contacted the U again. This time, he was told that “accommodations would be made and the university would try to be more mindful going forward,” he said, but the start date wouldn’t be moved because – per university policy – the calendar had already been set five years in advance.

Kaplan pushed back, emailing Dr. Thomas Chase, the chair of the U’s Senate Committee on Educational Policy (SCEP), and requesting that the committee reconsider the start date. The committee is responsible for approving the university’s academic calendar, though the Board of Regents could technically override any SCEP decision.

“Having provided the University with sufficient time to avoid having to make Jewish students choose between their faith and equal inclusion in the University calendar, I am not sure what else can be done to ensure mindfulness,” Kaplan wrote.

It was the first that Chase had heard about the start date conflict, as he had become the chair of SCEP only a few months earlier. “I knew it was going to be a difficult problem,” Chase later said in an interview. “But I hoped we might be able to come up with some kind of a solution. And as you know, we failed.”

No Way Out?

On Dec. 9, SCEP discussed what to do about the conflict, guided by a document prepared by Provost Rachel Croson’s office that outlined potential solutions to adjust the academic calendar for Rosh Hashanah.

According to Chase, the conversation took 40 minutes, which “is a long time for one of our meetings, because the meeting [is only] two hours. We devoted a substantial chunk of our meeting time to this issue. And it was contentious.”

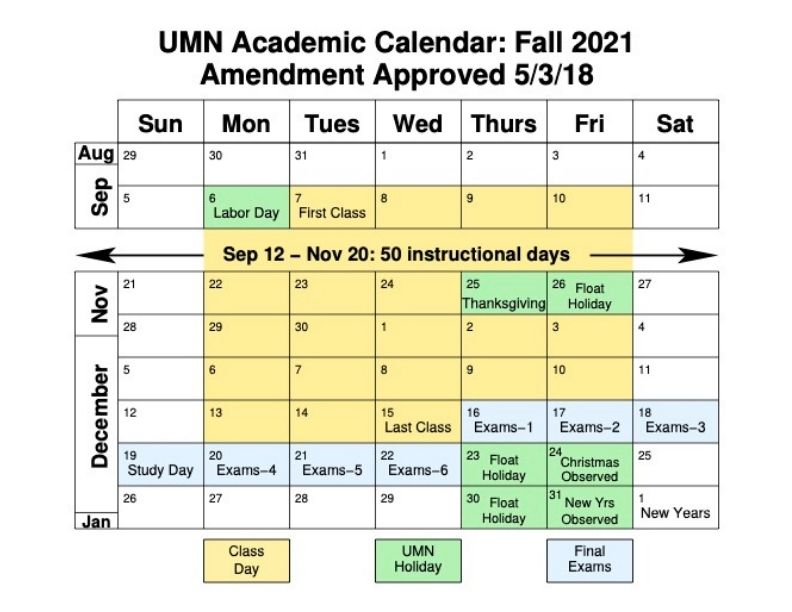

A guide to the fall 2021 semester calendar put together by Dr. Thomas Chase, the chair of SCEP, for the committee’s discussion on the Rosh Hashanah start date conflict. (Courtesy of Thomas Chase)

Solutions were brought up and shot down. The semester could be adjusted to start before Labor day, thus avoiding classes on Rosh Hashanah — but that would eat into freshman Welcome Week; disrupt the university’s contract with the State Fair to use the U’s parking facilities; negatively affect the travel plans and visa applications of international students. Shifting the calendar would also affect classes that are held once a week.

Simply canceling class for Rosh Hashanah wasn’t an option either — the university needs 70-75 instructional days per semester for accreditation, and the fall 2021 semester is already at 70 days.

The six days of final exams, which guarantee no more than two finals per day for students, plus one study day, also couldn’t be reduced to make room for Rosh Hashanah. Otherwise, students already experiencing high levels of academic-related stress and anxiety, would have a more stressful end to the semester.

For the same reason, changing the Friday after Thanksgiving from a holiday to a school day was not possible.

“I hadn’t imagined the number of reasons that it was nigh impossible to change the starting date,” Chase said.

Having heard enough, Chase held a straw poll asking if the start date should be adjusted. Six SCEP members voted yes and 10 voted no, sealing the university’s stance. In statements, the provost’s and president’s offices have both referenced the committee’s decision when explaining why the start date was not moved.

“Sometimes life is messy. And I think this is one of those situations,” Chase said. “I have no idea how those six would have solved the problem. We were eagerly inviting ideas of what can we do with this, and nobody had any suggestions.”

Cracks in the Process

Critics of the committee’s decision agree that it was messy — and say it was problematic, too.

“First of all, there was no one in the room really speaking for the Jewish experience,” said Natan Paradise, associate director of the U’s Center for Jewish Studies, who did not attend the Dec. 9 meeting but did read the meeting minutes.

“They were much more concerned about the potential inconvenience to pretty much everybody else if we move the start date, as opposed to what it meant for the Jewish community.”

The committee “never invited me, for example, or anybody else who could really speak as an educator about the Jewish experience and educate them about the implications of their decision,” Paradise said.

Chase agrees that, in hindsight, SCEP should have had a representative of the campus Jewish community speak at the meeting, though he says there was a Jewish committee member involved in the conversation (they were one of the six votes to move the start date).

But he disputes the idea that the committee didn’t know, or take seriously, what the start date conflict meant for Jews.

“It probably would have been a good idea to have someone from Hillel to speak…and I regret that we didn’t think of that,” Chase said. “And yet, I think that the Jewish voice very definitely was heard. We had multiple letters that had been forwarded either through the president’s office, the provost’s office, or sent directly to SCEP expressing the concerns. So going into the meeting, I felt pretty secure that I knew what the Jewish community wanted.”

The committee also ended any conversation about moving the start date with the straw poll, instead of consulting with other university organizations to see if anyone else had workable solutions. “By the end of the discussion, it seemed kind of not productive to extend the discussions because it just looked like it was not possible to do,” Chase said.

And, to the confusion of many Jews, SCEP’s discussion (and the provost’s guiding document) centered around the idea that the academic calendar had to be adjusted for both days of Rosh Hashanah, rather than just one day.

Though Rosh Hashanah is technically a two-day holiday, many families only observe the first day. As a result, the Jewish community’s campaign to get school districts to change their fall 2021 start dates was largely focused on shifting one day, and many districts did just that. Though Jews who observe both days would still have to miss school, “we felt like [one day] was a very reasonable request,” Roberts, of the JCRC, said.

The same feeling applied to Hillel’s request of the U, and Jews who suddenly learned about the emphasis on two days from university statements were baffled.

“We never asked for two days,” Stillman, Minnesota Hillel’s board president, said. “We just asked to not start school on the holiday…and I never heard that given as the reason, ‘we can’t give you two days so we can’t give you any days.’”

When asked if he knew the Jewish community wanted to adjust only one day, Chase was surprised. “I was not aware of that,” he said. “I thought that we needed to honor Rosh Hashanah through sunset of Wednesday.”

Nonetheless, he says that if the SCEP discussion had been about one day, “it would have been incrementally easier, but still extremely difficult” to change the academic calendar.

While one day versus two days might sound like a silly distinction, focusing on a one-day shift may have revealed a way to resolve the scheduling conflict that the university, it seems, did not consider.

After the semester ends, and before Christmas, is a “float holiday” scheduled for Dec. 23 on the U’s calendar. Theoretically, if that float holiday was moved to after Christmas, the semester could have been shifted by one day to run from Sept. 8 to Dec. 23 — leaving the first day of Rosh Hashanah start date-free.

When asked if that was an option, Chase said no, because the U makes a contract with unions about when holidays take place. “So if we tried to meet on that day, a lot of the staff wouldn’t have been present,” he said. “And I’m not sure it would even be possible to officially open the university.”

This implied that it would have been too difficult to negotiate with the unions to change the date of that float holiday. But Eric Salminen, an organizer for AFSCME Local 3800, representing the U’s clerical workers, contests that.

“By some super bizarre and disingenuous stretch [the U seems] to be trying to string together an idea that by changing [the] start date… [it would] then impact our holidays which the union has already been notified of, thus creating a link to the union,” Salminen said via email. “But that is enough of a stretch to be laughable, really.”

While the union has a legal right to bargain over the date change of a holiday, Salminen says it would not have been an issue.

“While certainly individual members may have some preference, I have never heard a peep one way or another on which day (the Thurs. or Fri. before, versus the Mon. or Tues. after Christmas) to be the day off,” he said. “They just mean sending one email is more work than they are willing to do.”

Chase did not respond to questions about if the unions were contacted before assuming it would not have been possible to change the float holiday and adjust the calendar for Rosh Hashanah.

In an emailed statement, Provost Croson said, “we discussed potential solutions with a number of constituents. These groups include Human Resources (who is responsible for negotiating with the unions), the Minnesota Student Association (the undergraduate student government), multiple faculty governance committees…representatives of the Jewish community and others.

“These conversations contemplated a variety of options, including those you’ve mentioned in your questions…and there were no possible alternatives that satisfied the needs of the academic calendar and all of these groups…as has been noted, the University’s calendar is the product of a complex system where we are required to have a certain number of class days (instructional days), weeks of classes in a term and accommodate a wide variety of educational formats and class meeting patterns.

“When we discussed this issue with the Senate Committee on Educational Policy and the Executive Director of Hillel, we talked about solutions involving both one day and two days of rescheduling. Neither proved to be feasible.”

Making Choices

Once the U decided not to change the start date, all attention turned to making sure Jewish students knew they could skip class to observe Rosh Hashanah without being penalized.

On one hand, Jewish students were already covered. The U has a policy that students have to attend the first day of their classes, or else they could lose their spot in class, but there is an exception for religious holidays that explicitly mentions Rosh Hashanah. Students just had to tell their professor about the excused absence.

Still, there were concerns about students being uncomfortable talking to professors about the holiday, or with new students just not knowing what their options were, Paradise, of the Center for Jewish Studies, said.

So with the help of Hillel and the CJS, the U also worked to set expectations with faculty. “We just [had] to make it absolutely clear that even if a student doesn’t follow this procedure, and they don’t go on the first day, they’re not going to lose their seat,” Paradise said.

As a result, students that did skip the first day of the semester had no issue doing so. But anecdotally, even with the extra effort for accommodations, many students still chose classes over services.

“While it was nice to know that I wouldn’t be academically penalized for missing class, I still was going to be missing important information if I chose to go to services instead,” Sophie Shapiro, Hillel student president, said in an email.

“I eventually decided to split my time between services and class…students often have to choose between going to classes and Hillel during the holidays, but having it fall on the first day was an added pressure,” she said.

Reuben Vizelman, president of the Chabad student board, chose to skip services entirely.

“We all come to school for a reason. We all want to get a degree, we want to learn, we want to graduate and get a job and all that stuff,” he said. “So anything that impedes that, like, whether it be missing class because of a religious thing, or because you’re sick…none of it’s an easy decision.”

Paradise is not surprised. “It’s one of the reasons that we’re so angry about [the U’s decision not to move the start date],” he said. “When students are forced to choose between their student identity and their Jewish identity, it’s always the case that many of them will choose the student identity, just because it’s so hard.”

Students had a wide variety of opinions on the start date conflict – while some were angry, there was also broad acceptance of the situation. For Vizelman, there aren’t enough Jews on campus to make it worth being upset.

“What’s me and other Jewish students protesting going to do in the long term,” Vizelman said. “It’s going to cause an issue for the U of M, it’s going to cause an issue for us, and at the end of the day…it just is impossible, the U of M is too big to really move things around for such a small population.”

Jewish faculty also struggled with the start of the semester. For Paradise, not working on Rosh Hashanah meant anxiety about if a student was trying to contact him, or about missing an important message from the university.

Paradise also lost a day of the intro to Jewish history class he is teaching this semester, and worked to adjust the syllabus to still give students the fullest possible experience.

“It’s always an issue, every year, for me,” he said. “I choose the days that I’m going to teach on by looking at the calendar and saying, ‘okay, what is the minimum number of classes I’ll have to cancel based on when the [holidays] fall this year.’”

But balancing the holidays with classes isn’t only restricted to Rosh Hashanah. One Orthodox Jewish junior in the Carlson School of Management is struggling to stay on top of coursework after missing class to observe all of the high holidays.

A mother of three, the student, who asked to stay anonymous, thought she could catch up by studying late at night, but “I simply can’t do so much in such a short time,” she said. She has missed six days of in-person lectures in a class that has an exam coming up on Oct. 4.

After Simchat Torah, she emailed the professor to ask if she could take the exam at a later date. “Sorry. We are on a tight timeline and have no leeway for a delay in delivery dates,” the professor replied.

“This is not [the] first time” this has happened to her, the student said. Professors “are simply unaware and have never heard of the Orthodox observance…they simply can’t think of any reason why someone would not be able to study for so much time.” She hopes that explaining her observance again will cause the professor to reconsider, but she’s not sure that will happen.

Paradise says this is an issue across the university. “There’s this idea that, okay, you’re not in class, but you can still do work on the day that you’re gone,” he said. “And that’s modeled on the Christian experience of holidays, where you go to church for an hour or two, and then you have a festive meal. And then you can’t wait to get away from your annoying uncle and watch a football game…that’s not the way our holidays work.”

Moving Forward

Despite a frustrating experience, Minnesota Jewish professionals are focusing on the future. Part of doing so is addressing the anger many Jews feel toward the U because of the start date conflict — some of which was expressed as accusations of antisemitism against the university.

Benjie Kaplan, Minnesota Hillel executive director, shows a rendering of the new front of the building on a 2019 tour. (File Photo by Lev Gringauz).

“It’s really important that we not look at it that way,” the JCRC’s Roberts said. “We have to be really sensitive to, anytime something doesn’t break our way as a community, throwing out the charge of antisemitism or impugning someone’s motives…we can’t be the community that cries wolf, [as if] we have one tool in our toolbox.”

And while the start date issue “surely doesn’t help” the U’s reputation among Jewish families and prospective students, the University of Minnesota is still a great campus for Jews, Kaplan said.

“Often we judge things only by the negatives we see and hear,” Kaplan said. But “when I look at the three Jewish Greek chapters on our campus, our robust Hillel and Chabad involvement, the 150 students we take to Israel each year (in non-pandemic times), the academic quality of our Jewish Studies program…I see one of the best campuses in the country for Jewish students.”

More scheduling challenges lie on the horizon for the university. In 2032, the second day of Rosh Hashanah will fall on the Tuesday after Labor Day, when most Minnesota schools start the school year.

And other Jewish holidays still risk important university events being scheduled on their dates, or, on a smaller scale, professors deciding to schedule exams on a holiday.

Provost Croson’s statement said that the U has put together a task force to review future academic calendars “to recommend adjustments for Rosh Hashanah and other religious and cultural holidays.” The guiding letter for the task force says “reducing that overlap can enhance inclusion and belonging…these holidays are important to both our internal and broader communities.”

To address future conflicts, Paradise said that the university also needs to have an expectation for all faculty and administrators to check the multifaith calendar kept by the Office of Equity and Diversity before scheduling anything. “If we can get everyone to make it part of their process to never do anything without consulting that calendar, that’s going to help,” he said.

It’s not the first time (and likely won’t be the last) that Jews prod the U about checking a calendar. In the 1980s, then-executive director of the JCRC Morton Ryweck sent many a five-year calendar to the university. But scheduling conflicts with Jewish holidays continued to happen — including under president Kenneth Keller, the first Jewish president of the U.

“What we know, obviously as a Jewish community, is that we have to advocate for ourselves,” Roberts said. “We do not have the luxury of just saying, well, this bad thing happened, so I’m just going to disengage.”

At the same time, “it’s not like the Jews are secret holders of this information as to what our holidays are,” he said. “Anyone could have checked the calendar, right?”

This piece received Honorable Mention in the category Excellence in Writing About News from the American Jewish Press Association’s 41st annual Simon Rockower Awards for Excellence in Jewish Journalism.

This piece received Honorable Mention in the category Excellence in Writing About News from the American Jewish Press Association’s 41st annual Simon Rockower Awards for Excellence in Jewish Journalism.

Great article.