In the early days of Jewish Community Action (JCA), then-executive director Victor “Vic” Rosenthal started advocating for an issue that few were rallying behind: driver’s licenses for all.

“Vic had talked to some people in the Latino community, and they were concerned about this issue of their driver’s licenses being taken away if they were not documented,” said Rep. Frank Hornstein (DFL-Minneapolis) a co-founder of JCA.

Amid the anti-immigrant sentiment of the early 2000s, it was an unpopular issue to take on. But to Rosenthal, that didn’t matter — JCA was obligated to be part of the advocacy coalition working on the cause.

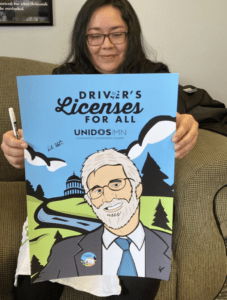

Emilia Gonzalez Avalos, the director of Unidos MN, holds a poster with Vic Rosenthal’s picture on it supporting Driver’s Licenses for All.

That work paid off only this year when Gov. Tim Walz signed a bill allowing undocumented Minnesotans to get driver’s licenses. At the signing ceremony, several people approached Hornstein to say, “Vic was such an ally for us,” Hornstein recalled. Unidos MN, an advocacy group key to passing the legislation, printed Rosenthal’s image on posters to celebrate the win and Rosenthal’s contribution.

Vic Rosenthal died on March 27 after a long fight with cancer. He was 68.

A transplant from New York City who maintained a lifelong love of the New York Yankees, Rosenthal made his mark on Minnesota as a co-founder and the first executive director of JCA, serving for 17 years in the role. He is remembered for mentoring a generation of activists and creating a nationally recognized model for Jewish community organizing.

“He was so grounded in a cultural expression of Judaism that was about…working for justice, and also building community,” said Carin Mrotz, who succeeded Rosenthal as JCA’s executive director from 2017-2022.

At the same time, Rosenthal was a devoted husband, father, and grandfather who supported his family with the signature loyalty and perseverance he applied to advocacy work. He coached basketball and soccer teams for his sons, Aaron and Ben, while they were growing up, and never missed a game they played at.

“It’s relatively rare for people to be able to devote so much of their life to work without neglecting certain family responsibilities,” Aaron said. “But he somehow managed to find a balance between the two.”

In Rosenthal’s marriage to Chris, his wife of 43 years, “he did the laundry, he was a partner in things,” she said. “He was always willing to step in and be a part of what we needed to do. So ahead of his time in that way — a lot of men never did that, but he did.”

Key to both his work and personal life was Rosenthal’s enduring sense of humor, and his ability to laugh at himself for things like a lack of fashion sense, brought on by his color blindness. It’s a quality that Wendy Christopher, Rosenthal’s sister, deeply misses as the family gathered to mourn him.

“Vic would have been one of the people to lead the conversation, and he would have had us laughing,” Christopher said. “He was just very clever.”

Right place, right time

Rosenthal’s path to Minnesota was, in a way, fate. In 1978, on a New York to California road trip with a friend, they made a stop at Jenny Lake in Grand Teton National Park.

There, the road trippers ran into a group of women — Chris and her friends — who were also traveling, and stopped to chat. Rosenthal instantly made an impression on Chris. He “had this very serious side, and then he was so funny,” she said. “I remember thinking, ‘what a wild combination.’”

Somehow, Rosenthal and Chris kept running into one another — once that evening while staying at the same campground, and again two days later in Sun Valley, Idaho, when Chris and her friends went out dancing. The two groups had planned to meet up in Sun Valley, but nearly missed each other.

“It was midnight, and we were at a bar…and who should walk in but Vic and his friend,” Chris said. “They’d been trying to reach us all day and had finally given up and said, ‘We’ll stop and have a beer.’”

Chris gave Rosenthal her address and headed back to her native Minnesota. Soon after, she got a letter from Rosenthal: Did she want to see him again? “Absolutely,” Chris replied. And after another near miss at the Minneapolis Airport — Rosenthal called at 2 a.m. to tell Chris he was flying in, but Chris didn’t remember when the flight was — they found each other for good and married in 1980.

But to figure out whether to settle around NYC, close to Rosenthal’s family, or Minnesota, with Chris’ family, the two made a deal: They would live six years in New Jersey, six years in Minnesota, and then decide.

“They did six years in New Jersey and then 36 years in Minnesota, so obviously my mom won that fight,” said Aaron, their son.

In time, Rosenthal would make Minnesota his own, and even get a commemorative day in St. Paul. But the first few years were tough as Rosenthal struggled to get used to the “Minnesota Nice” culture.

His New York habit of speaking his mind got Rosenthal in trouble with employers. “His bosses would say, ‘Vic, you have to tone it down here in Minnesota, you can’t use the strong words that you use,’” Chris said.

But soon, that East Coast outspokenness would become a beloved feature, not a bug, as Rosenthal made a life-changing move into Jewish social justice activism.

Mentoring JCA to life

In 1994, Frank Hornstein was part of a group of Twin Cities Jews trying to start up a Jewish social justice initiative. Looking for feedback, Hornstein reached out to community members for one-on-one conversations.

On a whim, he contacted Rosenthal, then the executive director of a nonprofit called the Minnesota Senior Federation, to set up a meeting.

“He greeted me so warmly and told me of his journey to advocacy,” Hornstein said. Rosenthal mentioned that he “had a strong Jewish identity, but never really connected that to his social justice work, and [that this Jewish initiative] was really interesting and intriguing to him.”

Rosenthal joined the organizing committee for what would become Jewish Community Action, and then took on the role of executive director to work full-time on growing the organization.

“There was a part of me that felt a little guilty that he took this risk,” Hornstein said. “He left a job as an executive director with an established organization…I didn’t know what [JCA’s] budget was gonna be, I didn’t know if we could sustain this position that he signed up for. But he was so enamored with this concept of a Jewish social justice organization that he risked a lot.”

Rosenthal’s family credits JCA with deepening his connection to Judaism, and bringing Rosenthal to see his Jewish identity and activism as one and the same. Though for some, his involvement came as a surprise.

“We didn’t grow up with that,” said Christopher, Rosenthal’s sister. “We lit candles for Hannukah, but there was no religious observance in our family…When he got really involved in JCA, I would not have expected that.”

Rosenthal’s newfound approach to his Judaism proved influential in setting the tone for JCA and helping to bring in Jews who didn’t feel at home in other parts of the community.

That’s what happened with Carin Mrotz, who applied to work at JCA in 2004 to escape a corporate job.

“I had been in Minnesota for seven years at this point, and…I had not really found Jewish community at all,” she said. But “I sat down with Vic, and I immediately was like, ‘Oh, I feel so comfortable, and for the first time in Minnesota, I can just be myself.’”

Hired as JCA’s office manager, Mrotz didn’t expect to be involved in the organization’s advocacy. But she underestimated another one of Rosenthal’s qualities: His drive to mentor everyone he came across. “I was there to manage the website and run payroll, and he immediately insisted that I be engaged in the organizing,” Mrotz said.

“Vic was the master of the term ‘voluntold,’ which is where you are forced to volunteer to do something,” she said. “It was so annoying. And in hindsight, I realized he was growing my leadership, my skill set. Vic…would just explain things to you, he would give you things to read, he would ask you questions, but he would also bring you in and require that you did hard work because he knew that it was going to teach you and make you better.”

Rosenthal’s mentoring — formal (teaching at Metro State University in St. Paul) and informal — helped many activists find their place in Minnesota’s social justice community.

“When I was a young organizer unsure of where I belonged in most mainstream spaces, I remember at a coalition meeting, settled in the back as an observer (my typical orientation),” tweeted Chanida Phaengdara Potter, the former executive director of the Southeast Asian Diaspora Project. “Vic scanned the room and yelled, ‘Chanida, where are you? We need you at this table!’”

Mrotz took over as executive director of JCA in 2017, and then handed the reins in 2022 over to Beth Gendler — who also credits Rosenthal with helping her develop leadership skills, like fundraising, when she previously headed the Minnesota chapter of the National Council of Jewish Women.

Rosenthal “was a relentless fundraiser,” Gendler said. “He had this amazing inability to hear the word no. I’ve heard some folks say that he would get legitimately angry if granting organizations and individuals [didn’t support JCA]…He let them hear about it.”

Even to longtime activists, Rosenthal’s willingness to be available for others was unique.

“I’ve been in situations myself, just starting out at different nonprofits, and my supervisor would always be like, too busy,” Hornstein said. Rosenthal “was never too busy…he just valued people and relationships.”

Legacy of action

In building JCA, Rosenthal redefined Jewish activism in Minnesota and, to some extent, nationally as well.

“JCA is really one of the flagship local Jewish social justice organizing projects in the country, in large part because of the work that Vic did to build it,” Hornstein said, noting Rosenthal’s rare ability to balance building a vision for the organization, mentoring staff, and being a competent administrator and fundraiser.

Rosenthal geared the organization toward building deep relationships with other minority communities, bringing JCA into key social justice coalitions, and pursuing a broad range of housing, economic, and racial justice advocacy.

Rosenthal also “had a vision of the way that local Jewish organizing should be a field,” Mrotz said, “and should be resourced and taken really seriously and seen for how crucial it is.”

It was with that vision in mind that Rosenthal supported other organizations like NCJW, and worked on an effort that would become The Collaborative for Jewish Organizing, a national network of grassroots Jewish social justice organizations.

“He really operated out of an abundance mindset before that was a nonprofit catchword,” Gendler said. “He truly believed that if progressive Jewish organizations in Minnesota were strong, we would strengthen each other…that we do better work when we do it together.”

Over the past few years, Rosenthal had also been working to organize and bring the JCA archives into the Upper Midwest Jewish Archives at the University of Minnesota. In doing so, he wrote a book with Michael Kuhne, a professor at the Minneapolis Community and Technical College, about JCA’s history and lessons from the organization’s advocacy. The manuscript for that book is now being shopped to publishers.

Meanwhile, JCA wants to find a permanent way to honor Rosenthal. Asked what they would like to see JCA do, both Chris and Aaron emphasized a focus on the work of community organizing.

“Some kind of award given to organizers who have shown a particular ability to address injustice, particularly individuals who might be working in coalition with others,” Aaron said. “It was always so important to my dad that the Jewish community work in coalition with other historically oppressed communities.”

An educational initiative, like a set of workshops about community organizing, would also be a fitting way to remember Rosenthal. “He was a firm believer in education as a tool for promoting social change, collective action,” Aaron said.

Aaron recalled another core quality that served Rosenthal in his personal and professional life: Not being afraid to show vulnerability.

When Aaron was around eight years old, he got into an argument with his father. Afterward, Rosenthal went to Aaron’s room to explain why he had argued.

“The next day he was flying somewhere, and really, the reason he thought he was arguing with me is that he felt so anxious about flying away and being away from family,” Aaron said.

During that conversation, Rosenthal cried. To Aaron, the story is emblematic of his father’s ability to connect with others.

“He was never afraid to show his anxiety, to show his insecurity…and that included his family, it included people that he worked with,” Aaron said.

“It’s part of what I think always drew people to him, that he was so willing to express his vulnerabilities in a way that defied a lot of stereotypes about men…and it left an impression on me that it’s important to be open in that way with people.”

Rosenthal is survived by his wife, Chris; his two sons, Ben (Megan) and Aaron (Florencia); two grandchildren, Harper and Henry; his sister, Wendy (Tony); and niece Carla.

1 comment