But – perhaps infamously – the University of Minnesota did not, sparking outcry in the Jewish community that veered into accusations of antisemitism and recalled the U’s history of bigotry towards minorities. The refusal was particularly jarring given the focus in recent years on diversity, equity, and inclusion in schools and universities.

The incident led Kate Dietrick, archivist for the Berman Upper Midwest Jewish Archives at the U, to check the historical records.

“I thought, ‘I’m pretty sure this has happened before,’” Dietrick said. “And [the U] apologized and said, ‘Never again.’”

After putting a few documents about previous start date-High Holiday conflicts on Facebook, and seeing the public interest in them, Dietrick decided the subject was worth fully researching.

“What can I do as an archivist to showcase archival documents as, yes, being part of the past, but also, very much being part of the present?” Dietrick thought.

Now, Dietrick’s findings – the product of a six week research leave – are on display in an exhibit titled “Symbolic Significance: Tracing the History of Jewish High Holidays and the First Day of School.”

The exhibit is available to see now until Jan. 30 on the third floor of the U’s Elmer L. Anderson Library. On Sept. 11, the library will host an official opening event with heavy appetizers, a Q & A with Dietrick as the curator, and a panel discussion (involving Minnesota Hillel, the Center for Jewish Studies, and the Jewish Relations Council of Minnesota and the Dakotas).

The exhibit showcases nearly 100 years of the Twin Cities Jewish community’s struggle to navigate school start dates clashing with High Holidays.

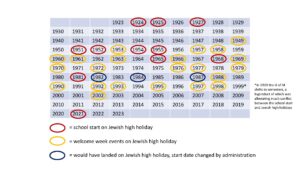

In that period, the U’s start date or welcome week events conflicted with High Holidays roughly one-third of the time – not counting several years in the 1980s when the university did change its start date to accommodate Jewish students and staff. Notably, the chance of that conflict was significantly reduced when the U switched from a quarterly to a semester calendar in the late 1990s.

An infographic compiled by Dietrick showing which years the U had conflicts with start dates or welcome week events, and High Holidays (Courtesy)

“I’m looking for Jewish community members to come here to hopefully, not only learn something, but also see themselves reflected…and see the archives that document their shared history,” Dietrick said.

“But I’m also hoping for a wider audience, people who don’t know what Rosh Hashanah is, [and who might think] ‘why is this a big deal?’ To learn and be like, ‘huh.’ I want that moment of stopping and reflecting.”

While much of the exhibit focuses on the University of Minnesota, Dietrick pulls archival documents about how the Jewish community dealt with conflicts in K-12 schools, too.

Some of that is focused around the “December Dilemma,” when schools celebrated Christmas and Jewish students had to sing Christian songs in choir proclaiming the birth of Christ. The clash of Christian environment and Jewish identity proved – and today still proves – stressful to students.

While the exhibit might be frustrating in showing that these conflicts are still not resolved, Dietrick also wants to be clear that, though incomplete, progress is visible.

She noted that over the last few years, several school districts in the Twin Cities have officially recognized Jewish and Muslim holidays in their calendars.

The exhibit is about “giving credit to all of the people that have had this conversation, and then [have had to do it again] the next year, and then the next year…this didn’t just magically happen. It’s through a lot of labor from a lot of different leaders.”

The documents that Dietrick dug up show several trends over the past 100 years. Among them is the University of Minnesota’s consistent approach in saying that yes, Jewish students are excused from the first day for High Holidays – but the students need to talk to their teachers and schedule their absence themselves. In 2021, the U took the same approach.

“What an onus to put on an 18-year-old kid who’s just left home, who is for the first time navigating their way through school, by themselves, and through potentially their access to their religion themselves,” Dietrick said.

Some professors might also not be as accommodating as the U says they should be, with one student writing in a 1981 letter that a professor thought of a Rosh Hashanah absence as “comparable to being gone for a basketball game.”

In the 1960s, this dilemma for students led to rabbis publicly calling for students to skip class and come to services. “Everyone recognizes that no other people in the world has made as many sacrifices for as many centuries as have the Jewish people in order to retain and perpetuate the Jewish faith,” one letter to a student reads.

In taking the absence on the first day, students “will demonstrate…that this faith is still meaningful and relevant in this time and place. I am confident that you will set an example of Jewish loyalty.”

The High Holiday-start date conflict also affected Jewish faculty and staff, with one letter from a U library employee in 1968 protesting her cut pay over her absence. “I was told that such absences are not ‘real’ holidays,” the staffer wrote.

In the 1980s, however, things changed. A conflict with the U’s start date in 1981 led to the calendar being shifted for ‘82, ‘84, and ‘87 to accommodate the High Holidays.

Some Jewish advocates were particularly “Minnesota nice” when pushing then-President C. Peter Magrath to adjust the start dates.

“I know that you are yourself extremely sensitive to the problems arising from such conflicts and anxious to avoid them, but it does appear that somewhere along the line, some scheduler does not share your own vigilance,” wrote one community member in a 1981 letter to Magrath.

Curiously, Magrath’s initial response was to say that the U couldn’t change any start dates due to the expense and confusion that shifting the calendar might cause (not dissimilar to the U’s reasons in 2021). But soon, he came around.

For Dietrick, putting together the exhibit felt a little strange amid severe concerns about antisemitism and extremism in the U.S.

But even if start date-High Holiday conflicts aren’t the most pressing issue, “this is a bellwether kind of thing that tells us how the community at large respects or thinks of Jewish community members,” she said.

“If you can’t get this right, if you don’t have respect for this – for the most important days of our religion – do you care about us as people?”

Looking at the chart, a lot of these timing issues occurred in the recent past. I don’t understand why having the conversation in 1981 and 82 wouldn’t have had an impactor the 90s: except of course, the U (and other universities and school districts across the country, it’s not just a MN issue) didn’t think it was important enough. It’s the 2021 date that’s the real shocker. All those years of goodwill down the drain. So dumb.

good article

Hey TCJewfolk. Do you know about my/our experience on this subject in Benicia, California in the summer of 1994? It was the previous time the day after labor day—-traditional school opening day—coincided with Day 1 RH.

I can tell you all about it…bottom line was a big hullaballoo but they changed after our urging.

Thank you.

Rabbi David Kopstein,

[email protected]

[email protected]