This is a guest post by Etan Newman.

This is a guest post by Etan Newman.

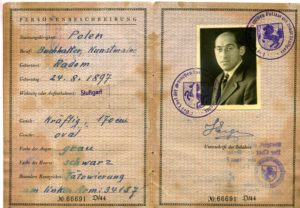

Seventy-one years ago today, in the early morning of April 28, 1942, my great-grandfather, Isaia Eiger, was arrested by the Gestapo in his hometown of Radom, Poland, and taken to Auschwitz. Over the next two and a half years there he would suffer beatings and hunger, join the resistance movement, and narrowly escape numerous brushes with death. But apart from a few anecdotes shared among our family, Isaia’s story remained buried for more than half a century.

“At about four o’clock [am] we heard the knock on our door—faint at first, then a bit louder…My heart stopped. There, in addition to the two Jewish policemen, stood the Chief of Gestapo, Sturmführer Scheggel. I knew that his presence meant danger…He asked me to identify myself and then asked the same of my young son, my wife, and my daughter, and ordered them to stay in their beds…As I was saying goodbye to my wife and children, the Gestapo man smiled as if to sneeringly ask, “You think you will see them again?”

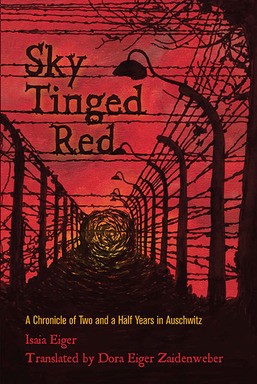

This scene is captured in the opening pages of Isaia Eiger’s newly published memoir, Sky Tinged Red: A Chronicle of Two and a Half Years in Auschwitz. I have read it ten times, and each time I am overcome anew with apprehension and fear: Will Isaia survive? Will he be reunited with his family? And then I correct myself: my family. Will my great-grandfather ever be reunited with my family?

I never met Isaia, but during the past three years I have come to know him well. As I read and re-read his story, I found a man whose humble narrative focuses not on himself but on the lives of those who did not survive. I met a leader whose ingenuity and compassion are revealed in his schemes to “organize” food and medicine for desperate fellow prisoners. I marveled at the bravery that led him to bargain for his life with an SS officer who discovered maps he made for the camp’s underground movement. And I was—and continue to be—inspired by my great-grandfather’s hope for the future, emanating even from the depths of a bunker where he was forced to sleep standing up for more than a week.

I never met Isaia, but during the past three years I have come to know him well. As I read and re-read his story, I found a man whose humble narrative focuses not on himself but on the lives of those who did not survive. I met a leader whose ingenuity and compassion are revealed in his schemes to “organize” food and medicine for desperate fellow prisoners. I marveled at the bravery that led him to bargain for his life with an SS officer who discovered maps he made for the camp’s underground movement. And I was—and continue to be—inspired by my great-grandfather’s hope for the future, emanating even from the depths of a bunker where he was forced to sleep standing up for more than a week.

If reading Isaia’s words introduced me to a remarkable man, preparing his book for publication imprinted his story within my very being. As I corrected typos and created paragraph breaks, I began to feel as if Isaia and I were in ongoing conversation. I listened to the lessons underlying his words and attempted to emulate his best qualities. Simultaneously, I found myself interpreting his words through the prism of my own values, silently nodding my approval of certain pronouncements and disavowing others.

This encounter with my ancestor was made possible only through the efforts of another hero: my grandmother (Nana), Dora Eiger Zaidenweber. After her father’s death in 1960, Nana had found the neatly bound pages of a manuscript, typewritten in Yiddish. She did not have time to sit down and translate her father’s chronicle until the 1980s. She then worked methodically, translating nearly 100 typed pages, until she reached the last page. But the narrative ended abruptly in the fall of 1942, long before Isaia was liberated. The rest of the story was absent. After checking and rechecking her father’s files, Nana eventually gave up looking.

Twenty years passed. Then, in 2007, before sending Isaia’s papers to the archives, my grandmother ventured one last look. Something caught her eye: a thick packet of papers handwritten in Yiddish script. She quickly realized what it was: the entire memoir!

Twenty years passed. Then, in 2007, before sending Isaia’s papers to the archives, my grandmother ventured one last look. Something caught her eye: a thick packet of papers handwritten in Yiddish script. She quickly realized what it was: the entire memoir!

I vividly remember the glee with which Nana informed us that she had finally found the remainder of her father’s writings. But with elation came despair. Nana was now legally blind. Reading through Isaia’s tiny script would be an arduous task; translating the un-typed section a nearly impossible one.

Calling my grandmother’s efforts over the next year superhuman would be an understatement. For eight hours a day she sat with a reading machine that enlarged each letter exponentially. Letter by letter, word by word, she translated the rest of her father’s story. She finished in ten months.

Nana’s herculean effort to bring to life her father’s words spurred the family to action. We proofread and edited the manuscript. My brother composed a foreword and afterword, based on interviews with Nana, about her family’s life before and after the war—up through their emigration to Minneapolis. Friends helped in the editing, drew maps, designed the interior of the book, and painted a beautiful original cover. And family members and friends recorded an audio book for Nana so she could finally “read” her father’s chronicle in its entirety.

With the book’s publication this month, Isaia’s words will finally reach the wider public. People everywhere can now read of his arrival in Birkenau when it was still under construction and follow its transformation into a death camp where entire communities perished. They can learn painfully of the beatings and horrors perpetrated not only by the Nazi captors, but also by prisoners against each other. And they can meet scores of comrades who refused to surrender their dignity, and instead bound together in mutual support and both spiritual and physical resistance to oppression.

But I believe that Sky Tinged Red is not simply one man’s account of struggle and survival. I have come to understand this book, released seventy-one years after Isaia was torn from his home that night, as a sort of ultimate reunion of my great-grandfather with his family and descendants. Through its publication, three generations of my family have been reacquainted with Isaia. More importantly, as together we have unearthed our ancestor’s words, his story has become our story, melding together generations of memory and experience into a family narrative that will endure far into the future.

Sky Tinged Red: A Chronicle of Two and a Half Years in Auschwitz (Beaver’s Pond Press, 2013) is available for order online through the publisher and on Amazon.

Etan Newman is a proud Minnesota native currently in law school in NYC. To learn more about his great-grandfather and the process of bringing his chronicle to life, please visit our website.