This is part 2 of Exodus and Equity: Reconciling the History of Minneapolis’ Jewish North Side, a series exploring how Twin Cities Jews were unwitting participants in racist real estate policies that shape today’s inequality in Minneapolis and other Midwestern American cities. In Minneapolis, that history is predominantly tied to two regions — Near North Minneapolis and St. Louis Park — and centered around civil unrest on Plymouth Avenue, in Near North, in the late 1960s.

—

If ever there was a time that Jews and Black people shared a similar experience of inequality in Minneapolis, it was in the first half of the 20th century.

Both firmly in the minority — by 1910, there were roughly 13,000 Jews and 2,700 Black people in a city of 301,408 — they were turned away from jobs, property, labor unions, and clubs. At that time, most Jews lived in North Minneapolis, where much of the Black community would soon join them.

Journalist Carey McWilliams would later christen Minneapolis the anti-Semitic capital of the United States, where an “‘iron curtain’ separates Jews from non-Jews.” (More accurately, white non-Jews.)

Journalist Carey McWilliams would later christen Minneapolis the anti-Semitic capital of the United States, where an “‘iron curtain’ separates Jews from non-Jews.” (More accurately, white non-Jews.)

But the shared experience of inequality wouldn’t last, and slowly the iron curtain lifted.

In the mid-20th century, even in the most anti-Semitic city in the nation, Jews were able to gain freedom of movement and leave the city (and its discrimination) for the suburbs. By contrast, Black people were trapped in formerly-Jewish city neighborhoods that became entrenched in long-term poverty. The legacy of this process is Jewish opportunity, and racial inequality, in cities like Minneapolis today.

Both stories hinge on a tool of discrimination that would become federal and systemic American policy: Legal clauses in property deeds, called covenants, that restricted ownership and rent of property to whites only.

The separate paths forged by these property restrictions contribute to the complicated way Jewish and Black communities — seen in Jewish cultural memory to be natural allies for civil rights — interact with each other today.

“There’s still this nostalgia in the Jewish community [in Minnesota] for the old North Minneapolis, ‘it was great, we were all in it together,’” says Dr. Kirsten Delegard, a historian at the University of Minnesota who co-founded the Mapping Prejudice Project, which tracks the history of covenants in Hennepin County.

“And I think a lot of African Americans are like, ‘but, wait a minute, you left when you could, and you actually benefited a lot from leaving,’” she said. “And there’s just been this ongoing inability to bridge those very different understandings of the history that continues to fester today.”

The earliest covenant found in Minneapolis, according to the Mapping Prejudice Project, is from 1910. Henry and Leonora Scott sold a house in South Minneapolis with a deed that said the “premises shall not at any time be conveyed, mortgaged or leased to any person or persons of Chinese, Japanese, Moorish, Turkish, Negro, Mongolian or African blood or descent.”

Soon, covenants dominated new real estate, and segregated whites from non-whites.

“By the late 1920s and the early 1930s they’re absolutely standard practice,” said Delegard. “Every new property that comes online…in the county has this kind of racial restriction attached to it.”

Due to the covenants, Black Americans were unable to buy or rent property in much of the city. And, in areas without covenants, they were pressured (often violently) by neighbors to move out of white neighborhoods.

Census maps created by Mapping Prejudice show the result: The Black population in Minneapolis became quickly concentrated around the North Side region known as Near North, roughly between Glenwood Avenue and Plymouth Avenue. And the surrounding white neighborhoods became whiter.

At the time, Near North was an ethnic enclave in the spirit of New York City’s Lower East Side, like many neighborhoods across northern cities. Generally poor, home to diverse groups of new immigrants, and with a reputation for being Jewish. By 1936, roughly 70% of Minneapolis’ Jews would live there.

In Near North, there were no covenants, which led to co-existence; and there was none of the violent opposition to Black migration found in white neighborhoods. For both Jews and Black people, there weren’t many other places to go. Early Minneapolis covenants banned property ownership by people of the “Semitic” and “Hebrew” race, too.

But Jews and covenants wouldn’t be at odds for long.

After seeing antisemitic covenants advertised in the Minneapolis Tribune in 1919, lawyer Emanuel Cohen lobbied the state legislature to address the practice.

The legislature did — via a law Cohen championed — that banned religious, rather than racial, discrimination in real estate. As a result, only 1% of the 30,000 covenants found by the Mapping Prejudice Project in Minneapolis were explicitly directed at Jews.

Despite the legal victory, Cohen’s 1919 law didn’t end discrimination in practice. Real estate steering and ground-level anti-Semitism continued. But the law did hint that Jewish and Black Americans would come to experience different real estate markets.

Where early covenants had listed all the races that were banned from a property, from the 1930s onwards most covenants banned only one explicit category of people: Non-whites.

A 1942 covenant deed that restricts non-whites from owning the property. (Courtesy Mapping Prejudice).

“That kind of signals, legally, a more bulletproof way to be racist,” says Maggie Mills, a researcher and map-developer for Mapping Prejudice. But the change in covenant language also meant a “shift in understanding; there’s a power in deciding who is white.”

Black people could never buy covenanted properties, with early language or otherwise. But Jews — at first in theory, and then in practice — could and did.

By the late-1930s, some Jews had already moved into a nascent St. Louis Park. According to the Mapping Prejudice Project, the houses they bought were covenanted, forbidding the property from being “sold, mortgaged, or leased to or occupied by any person or persons other than members of the caucasian race.”

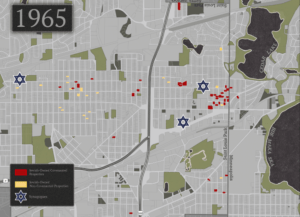

Maps developed by Mapping Prejudice show a few (but by no means all) of the known covenanted properties owned by Jews in St. Louis Park, and how the amount changed over time between 1936 and 1965.

1965 Map of Jewish-owned homes in St. Louis Park (Graphic courtesy of Marguerite Mills, “Exodus,” 2020.)

1936 Map of Jewish-owned homes in St. Louis Park (Graphic courtesy of Marguerite Mills, “Exodus,” 2020.)

For St. Louis Park, and the first-ring suburbs of other Midwestern and northern cities, covenants became a defining characteristic in the post-World War II housing boom and the rise of suburbia. Access to covenanted houses meant that Jews had somewhere to go if they wanted to leave their metropolitan neighborhoods. Not everywhere — some suburbs in Hennepin County, like Edina, still excluded Jews — but somewhere.

But it was one thing to have access to property, and another to have the means to buy it. And that’s where the Federal Housing Administration came in, and institutionalized covenants through redlining.

The FHA was formed in 1934 as one of many federal programs meant to help Americans weather the Great Depression, tasked with making it easier and cheaper for Americans to borrow money to buy a house.

The FHA used federal money to insure property mortgages, allowing for favorable loan terms for homebuyers. As a result, more families gained access to inter-generational property wealth.

But the FHA wanted to make sure they were helping people buy a house in places where housing value would increase.

So, “in order to decide which mortgages are good investments, and which mortgages are bad investments, this new federal bureaucracy had to come up with a rubric for deciding what’s ‘safe’ and what’s ‘not safe,’” Delegard said.

That rubric centered on race and region. Real estate professionals in cities across the country were recruited to map out local neighborhoods, and color grade them by the likelihood of increasing housing value. Green marked the best neighborhoods; blue the second-best; yellow meant a declining neighborhood; and red marked a region too dangerous for financing.

Neighborhoods with Black people, or other non-whites, were marked on maps in red under the (false) assumption that they automatically lowered property value — thus, redlining. With that rating came a refusal to offer FHA loans.

“But the only way you could get the best rating, the green rating, was if you had racial covenants in place,” Delegard said. “So that redlining, that act of grading different neighborhoods, institutionalized this practice of racial covenants. Because it was at that moment when the federal government said, ‘if you want these really favorable loan terms…you have to make sure any development is racially exclusive for white people.’”

Residential segregation became more entrenched, as did the notion that white areas were worth investing in, and Black areas were not.

As a result, real estate developers, in the post-WWII housing boom that built up suburbs like St. Louis Park, blanketed new homes with covenants.

This was advantageous for the Jews who would move there. With the help of the G.I. Bill, which offered FHA loans to WWII veterans, buying a house in St. Louis Park was cheaper than renting in Near North.

And, according to a recent study of housing prices, covenanted homes in the Minneapolis area, on average, are worth 4-15% more today than identical homes without covenants.

In real estate, every cent makes a difference. Houses in St. Louis Park that could be bought in the 1950s for around $10,000 are now worth upwards of $300,000.

But while Jews benefited, left North Minneapolis, and helped St. Louis Park develop a national reputation for tolerance, stability, and wealth (championed by home-grown heroes like journalist Tom Friedman, the filmmaking Coen brothers, and best-selling author Peggy Orenstein), redlining would wreak havoc on the Black community in Near North.

For all the talk of tolerance, “St. Louis Park was as complicit in keeping Blacks out, and confined to North Minneapolis, as any other majority-white community in the Twin Cities,” said Russell Star-Lack, a recent graduate of Carleton College who wrote his senior thesis on the Minneapolis Jewish community’s migration to suburbia.

To be clear, “it’s not like the Jews were the orchestrators of this system,” Star-Lack said, or the only people who benefited through racist real estate policies. “We’re not special; that’s what every immigrant group in this country did.”.

Unable to access covenanted properties outside of Near North, real estate agents gouged housing prices and rent. Without an FHA loan to buy a house, many Black Americans spent more money renting, without access to the property wealth gained by homeownership. Properties became more run down, with a higher population density and lack of funds to repair old homes.

As a result, a 1947 housing study found a “disproportion of overcrowded and substandard housing possessed by the minority populations” in North Minneapolis. Redlining became a self-fulfilling prophecy. By cutting off financial help, neighborhoods the FHA thought would decline in property value, did so. Poverty and instability swept the area, bringing heavier police presence and aggression.

Though covenants were ruled unenforceable by the Supreme Court in 1948, and Minnesota banned them in 1953, redlining continued. Even after the 2008 economic and housing recession, reports show that banks steered minority homeowners toward low-quality mortgages, and were more likely to deny them mortgages altogether.

And as a matter of practice, even Black WWII veterans eligible for an FHA loan under the G.I. Bill could not get a loan to buy property in a white area like the suburbs, said Delegard.

Conditions in Near North would only deteriorate further — eventually leading to explosive civil unrest on Plymouth Avenue in 1966 and 67, as Black North-Siders protested the discrimination and poverty they faced. By that point, most Jews had already moved to St. Louis Park, and those who remained in Near North fled there as well.

Redlining kept Black families in Near North mired in poverty, and away from the opportunity of suburban property wealth and stability, while Jews paid a special price for attaining the American Dream in the suburbs, Star-Lack said: “Being the face of these [late-60s] confrontations…not just in North Minneapolis. In many American cities.”

This has been an excellent series – very clear, well-written and timely. Thank you.